Aristophanes wrote raucous comedies. De Troyes, Shakespeare, and Dante wrote in their vernaculars. Mozart wrote operas, Beethoven symphonies. Georges Méliès made fantastic science fiction films, and hundreds of men and women participated in the pulp magazine fiction craze of the early twentieth century.

All of these creators wrote, composed, and filmed classics — at least in retrospect. The powers that be found them vulgar, shocking, outrageous, made for the uneducated masses; in a word: lowbrow. For most media consumers living in the twentieth century, comic books embodied the artistic opposite of high culture.

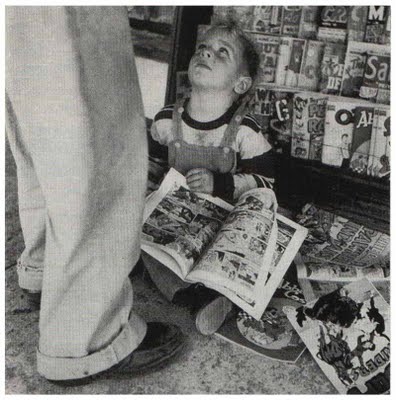

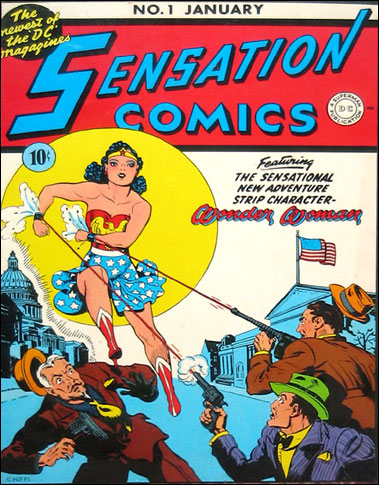

Comics of the early twentieth century were consumed in large part by children. Creators of the 1940s like Bob Kane and William Moulton Marston, now heralded inventors of Batman and Wonder Woman, wrote for children.

Marston, in fact, wrote in “The Family Circle” in an article entitled “Don’t Laugh at Comics” that comics had enormous educational potential for children. Accordingly, he created Wonder Woman to serve as a role model for young girls. Meanwhile characters like Batman’s Robin and Captain Marvel (the adult, superheroic alter-ego of teenager Billy Batson) served as the literary selves of adolescent readers.

Though Kane and Marston were, in a sense, writing for children, Marston also recognized that comics are for everyone! In a 1944 article entitled “Why 100,000,000 Americans Read Comics” Marston argued that half of this number was adults.

If this were the case, he asked, “Can it be that 100,000,000 Americans are morons?” He suggested instead that comics’ combination of word and picture triggered a primitive sensation that satisfied the mind in an emotional way that transcended notions of high or low art.

Marston’s words do not hold up today — after all, his comparison of comics to cave paintings and pre-literate societies is absurd — but its contemporary essence remains: comics are a separate artform with its own standards, and they are not only for kids.

Still, comics’ trite dialogue and gaudy images led many to believe they were for children, while some sought through statistical analysis to show that comics boasted a vast vocabulary that could improve language faculties. Education theorists went back and forth over the issue of whether to indulge comics as an educational apparatus or leave them out of the classroom.

Today the comic book industry, like the literati and artists attempting to create literary, filmic, and other artistic classics in the present, is not a faultless cultural producer.

Unlike other industries, the comics industry produces at an intensely fast rate, with some creators drawing thirty to sixty pages or writing three times that many pages of comic book script per month. Not surprisingly, comic books are sometimes the victim of inattentive editors, overworked writers, and underpaid artists.

In fact, when the medium is so little guarded that editors at companies like Dynamite routinely make major mistakes — like printing and shipping 75,000 copies of a sold-out, much-anticipated comic (“Red Sonja” #1) without crediting an artist, and instead labelling the artist the writer — it’s no wonder that literary snobs and highbrow art consumers look upon comics as a field of indigent wannabes towered over by the rare talents of Neil Gaiman (“Sandman”) or Art Spiegelman (“Maus”).

Luckily, the sort of major editorial mishaps quite prevalent at Dynamite tend not to occur at the Big Two (or Image and Dark Horse, for that matter) since they are subject not only to greater market demands, but also to their shareholders in the boardrooms of the Walt Disney (Marvel) and Time-Warner (DC) corporations.

In 2013 it is rare for passersby to be hostile toward comics readers or to look negatively on adults reading comics (within certain constraints; for example, a large, pimply, bearded fella reading “Aquaman” might not be a welcome neighbor on the T due to obvious biases). It’s doubtful any but the most conservative of parents would eschew their children reading a comic book.

This change toward the acceptance of comics is not so much a reflection of comics themselves, but is instead a general cultural confusion about comic books’ status as highbrow or lowbrow entertainment.

Today’s literati are more concerned with reality television, electronic dance music, Miley Cyrus, and text messaging than comic books — at least comics are reading material!

Additionally, comics are relatively invisible in the highbrow/lowbrow distinction because of the widespread cross-class and cross-gender appeal of superhero films and their recognized value in contemporary cinema.

The problem of placing comic books in a hierarchy of entertainment has been erased in the same way that early critiques of “Harry Potter” as promoting witchcraft no longer seem valid.

Comics, after all, can be found in high school classrooms in their more respectable format, the graphic novel, and their filmic counterparts are the recipients of Academy Awards. The cultural critics, in other words, have moved on from comics to less easily defended prey.

Positioned between high and low art, comics today are what literary historian Peter Swirski calls “nobrow,” meaning that they appeal simultaneously to both aesthetics.

While you can find comics on high school and university syllabi or winning literary awards, comic books remain just as awkwardly placed in the cultural hierarchy as their nerdy readers in the social hierarchy.

After all, you can read “Maus” and “Persepolis” with your tea-and-crumpet book club or write a term paper on “Watchmen” in your senior seminar, but still hear a laugh track mocking “The Big Bang Theory” protagonists for having a comic book collection.