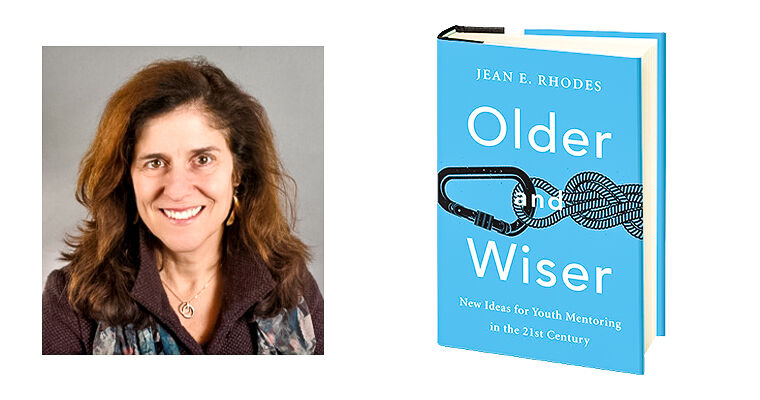

Jean Rhodes, the Frank L. Boyden Professor of Psychology and the Director of the Center for Evidence-based Mentoring, recently won Eleanor Maccoby Book Award for her book, “Older and Wiser: New Ideas for Youth Mentoring in the 21st Century.” The prestigious award was conferred by the American Psychological Association’s Developmental Psychology Division. The Mass Media had the pleasure of interviewing Professor Rhodes about her book and her journey of exploring the subject of youth mentoring.

Kaushar Barejiya: For our readers, would you mind introducing yourself and talking a little bit about your work here at UMass Boston?

Jean Rhodes: Well, I am the Frank L. Boyden Professor of Psychology and the Director of the Center for Evidence-based Mentoring. And I am a clinical psychologist by training. So, I am in the Ph.D. program and the clinical psych Ph.D. program through the psychology department. And I am currently working on a number of projects related to youth mentoring and to student mentoring. One is kind of evaluating what we’re doing over at Northeastern, you know, various what you might call behavioral economics projects where we tweak something and we see how it works, nudging students and such. I’m working on meta-analysis, group mentoring and coaching technology-delivered intervention. And then, you know, various projects where we’re looking at sort of the underlying mechanisms by which mentors are having their effect on mental health outcomes.

KB: For those who may not know, will you please provide an excerpt of your book “Older and Wiser?”

JR: So, the book is a compilation of 30 years of my research on the topic of youth mentoring, and it’s both formal mentoring like Big Brothers, Big Sisters kind of programs where you arrange a match between a young person and a volunteer, as well as informal mentoring, like the relationships that college students form with their professors or advisors, or high school students form with their coaches. And so, we’re looking at sort of the full spectrum of these supportive, non-parent caring people and how they support people. And a lot of this research came out of the Center for Evidence-based Mentoring, which is at UMass Boston. And so, it’s not just my research. It’s my doctoral student, my post-docs, my undergraduates and so forth.

KB: 30 years of empirical research is undoubtedly a long time. How was the process for you and what motivated you to embark on this journey?

JR: So, you know, it’s funny, the topic sometimes comes to you. And for me, I had a very important mentor. His name was George, and he was the founder of this field called Community Psychology, and he was my mentor during college. And his daughter actually became my best friend and remains a very close friend. So, at a very critical point in my intellectual development and identity development, I had a mentor. Then I went off to graduate school and I was doing a study on the kind of people who were resilient despite a lot of trauma and marginalization and difficulty. And what I found again was that one good relationship could make a huge amount of difference in terms of protecting people from the negative effects of stress. And so I dug deeper and there really wasn’t much of a field on this. There were people who had observed it, but nobody had really studied it as its own topic yet, because it was a long time ago. And so I began to look. I started with some very basic questions, like, you know, can these programs ever create what young people find on their own? Like, you know, a young person finds a coach or a religious leader or a neighbor who’s very important to them? Is that the same as what we create through programs and what kinds of people form these important mentoring relationships? And, you know, is it like kids who have had good relationships in the past, so they have trust, or is it people who really need it because they haven’t had good relationships and, you know, just a million questions. So, I got some funding and I went out and I studied formal and informal relationships, and that just led to more and more questions. And as I grew as a professor, I brought in more students and my students then went off and set up their research studies and the field really blossomed.

KB: Do you think college students appreciate the presence of a mentor in their lives, or are they still hesitant to call for help about non-academic problems?

JR: I think that you know, young people who are more privileged, who grow up in middle-class families and have parents that are, you know, really invested in their future, kind of teach them the strategies for building a social network. They’re like, you know, your summer’s coming up. You should reach out to my colleague at work or, you know, you should talk to your teacher about that. Whereas less privileged youth who grew up in poverty, who grew up at a disadvantage, first of all, there are fewer caring adults around. The ratio of teachers to students is different. The ratio of athletic coaches to students is different. So, they don’t have as many opportunities, and they don’t necessarily feel the same sense of entitlement. For many of the students that we’ve studied over the years, including UMass Boston students, they can sometimes equate help seeking with weakness and feel like they’ve kind of been told, you know, you should be able to do this on your own. And they don’t recognize the importance of having a mentor. So we actually have a course that’s being offered at UMass Boston right now, like five sections of it called Connected Futures, where we actually work with students to teach them the value of mentors and then work through the strategies that more privilege youth kind of get on their own or through their families of like, here’s how you reach out, here’s how you send an email, here’s how you handle rejection, here’s how you describe your interests, here’s how you ask for things. And we’re finding that that makes a difference in students’ sense of belonging at the university in their sense of, you know, feeling connected to other people in their social networks. And we also find that, you know, a year later, they have a higher-grade point average. So, we do think it’s not something that comes naturally to everyone, but that it could be taught.

Professor Rhodes also founded a non-profit organization, MentorHub. MentorHub connects mentors and mentees through the app, enabling them to interact with each other. A web-based portal is used to link the program employees as well. Unparalleled levels of communication and transparency between mentees, mentors, and their programs are made possible by this seamless multi-platform connection.

UMass Boston Chancellor Marcelo Suárez-Orozco congratulated Rhodes on her accomplishment. “Jean Rhodes is a world-renowned scholar working at the cutting edge of her field. I congratulate her on this very prestigious prize,” commented Suárez-Orozco.

UMass Boston professor wins Maccoby Book Award

About the Writer

Kaushar Barejiya, News Editor