When we think “social justice,” we usually think about rallies, protests, and essays fighting for people’s rights. But it’s important to keep in mind that the fight for equality manifests in many forms, especially in the arts. Art becomes a way not only to demonstrate suffering, but as a way to demonstrate resistance and to open up dialogue between people.

Considering current international events, it’s fitting that for the week of November 16th to 20th, the University of Massachusetts Boston campus will offer social justice related events.

One of these events featured a talk titled, “Transnational Influence of the Black Arts Movement on Aboriginal Australians in the Era of Black Power.” The talk was held on the third floor of the Campus Center November 19th as part of the Center for the Study of Humanities, Culture, and Society Speaker Series.

Fulbright student in 2013 and Ph.D candidate at UMass Amherst, Alex Carter spoke in regards to his research on the relationship between African Americans and Aboriginal Australians in a transnational movement for their rights in the ‘60s and ‘70s, a relationship primarily built through art.

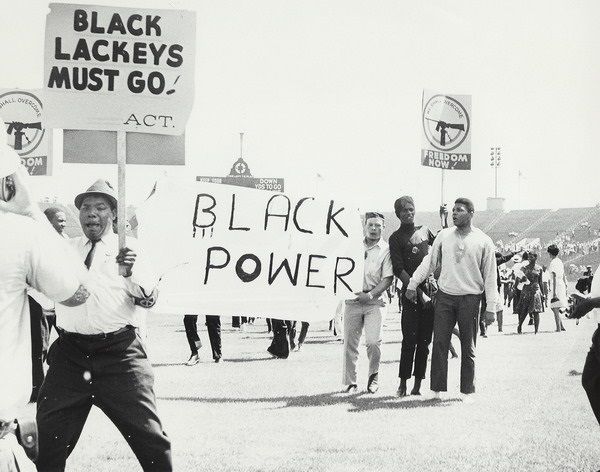

Carter’s initial introduction to the cause began with his own family’s connections to the Black Power Movement. As he learned more about groups like the Black Panthers, he began to wonder about the relationship between the civil rights movement in the United States and struggles for civil rights in other parts of the world.

“There’s uncovered history of Aboriginal Australians and African Americans working together in the ‘60s and ‘70s,” Carter said. The more he found, the more he kept digging, looking for more.

He found that the Black Power Movement was not grounded in the U.S. Rather, traces of the movement were found in England, India, and even Israel.

Quoting Nico Slate, author of “Black Power Beyond Borders,” Carter says, “‘Seeing Black Power in a global perspective means more than adding new characters to an old story. As Black Power moved abroad, and the meaning of blackness changed, there were new forms of unity and collaboration. Not just for African Americans, but for a range of oppressed people across the world.'”

As it turns out, art became an important way to spread the ideas of the Black Power Movement. The Black Arts Movement developed from this notion of using art as a vessel, and essentially began with Amiri Baraka’s theater school after Malcom X’s assassination.

“This movement is the aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept. As such, it envisions an art that speaks directly to the needs and aspirations of Black America. This correlates directly to the Afro-American’s desire for self-determination,” Carter said, quoting the Black Power Movement’s early theorist, Larry Neal.

Carter’s interest lies in examining how these movements manifest on an international level, and how blackness can be defined in different societies and cultures.

Richard Slamba, author of “Transcultural Journey,” defines transculturalism as, “rooted in the pursuit to find shared interest in common values across cultural and national borders.”

Aboriginal Black Power activists and U.S. Black Power activists saw in each other the same brutal histories and the same sense of being robbed of everything. Crucial forces of the movement taking off in Australia involved Aboriginal activist representatives attending Black Power conferences in the United States.

Carter explained that he focused on the actions of Bob Maza, a key figure in the movement for Australian Aboriginal rights. Maza was influenced by the Black Arts Movement while visiting the United States and inspired to develop Black theater in Australia. This was eventually expressed in the National Black Theater of Sydney, which was created to serve as the centerpiece for the Australian Black Power Movement.

The Movement in Australia was, and still is, focused particularly on Aboriginal land rights and self-determination.

“In 1967, the Australian Constitutional Referendum supposedly marked a new period in Australian history that displayed the Commonwealth’s movement towards a more just and inclusive society for Aboriginal people. What the referendum did was allow for Aboriginal people to be included in the census, to which they weren’t. And this is 1969. The Australian census did not count Aboriginal people as people in 1969,” Carter explained.

Art, particularly drama at the time, often repeated the famous phrase, “it’s nation time,” to remind oppressed Blacks that it was time to come together as a nation, within a nation. African American literature had a huge impact on the still-developing Aboriginal movement.

Many cultural phrases from the Black Power Movement of America, such as, “Black is beautiful,” were used to promote unity between Australian Aboriginals.

Although the Aboriginal people of Australia began to use the arts to help their cause, their circumstances have changed very little. Still today, the impoverished minority of 1 percent live in disease-ridden tin houses.

Due to a certain material used for the creation of iPhones, Apple’s champion product, the Australian government continues to push the Aboriginals off land that belonged to their ancestors, all while refusing aid.

However, despite the fact that the Aboriginals still struggle for their rights today, the coordination between African Americans and different Black people around the world has created a sense of hope. It is apparent that the oppressed groups of the globe are just as interested in helping one another as they are in helping their own.

Art becomes a way to communicate pain across language and geographical barriers. It is an important tool in paving the way for change.

Transculturalism and the Power of Art to Unite

November 20, 2015

Black Power Movement