Walking down the aisle at graduation, paired with Robert Redford, cameras flashing everywhere, video cameras stuck in front of his face, Richard Rooney smiled till his ears ached.

“They’re all bypassing me, and going straight for Robert,” he says. “We chuckled on the stage about that.”

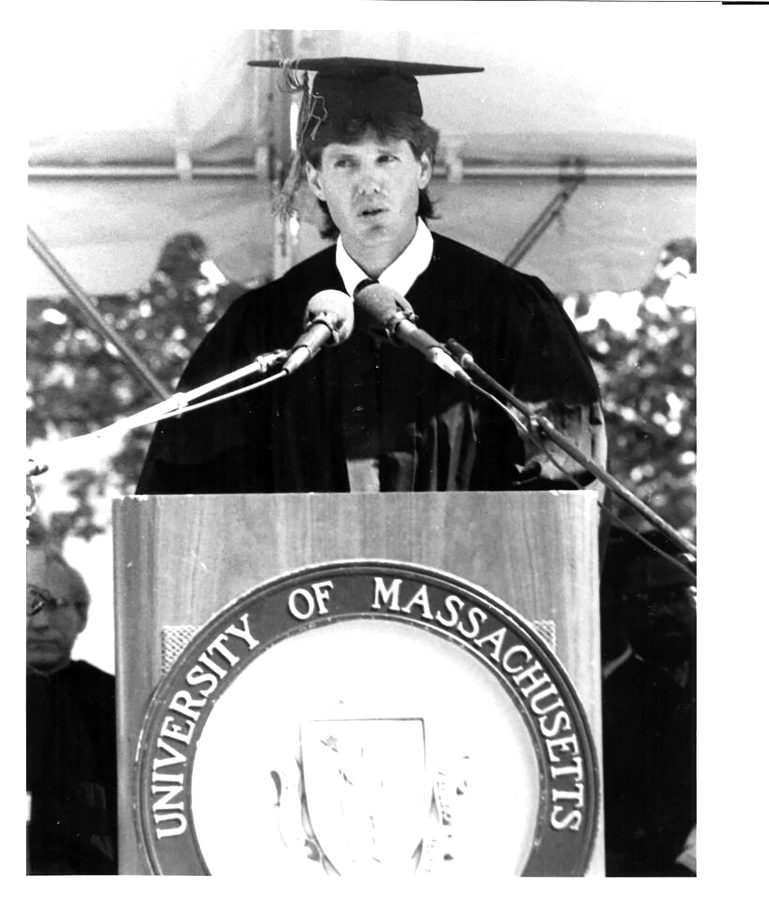

Redford got an honorary doctorate with the first graduating class from the Environmental Sciences program. Rooney was giving the graduation speech as the University of Massachusetts Boston’s Student Trustee.

“There were maybe about 100 or more faculty members on one side, all in their university gowns,” Rooney says. “I was, five years before, sitting on the fence in Humarock, wondering what the heck I’m going to do with my life. Now here I am giving my graduation speech.”

He spoke about the fight for public higher education funding that had propelled him to the stage. The UMass system fended off massive budget cuts at the end of the 80s and early 90s, and Richard Rooney took a vocal role in preventing fee hikes.

“We’re talking about 200 million out of [a] 700 million dollar budget,” he says. “It was devastating, and that’s what prompted outrage statewide. It was a very loud, chaotic period in higher ed.”

Rooney grew up in the Humarock section of Marshfield, a seaside community on the South Shore. He didn’t take much interest in high school, and spent a few years working before visiting UMass Boston on a friend’s suggestion when he was 25.

“When I first approached the university for admission I was denied,” he says. “The Admissions Office looked at my failing transcripts and recommended that I attend a community college and demonstrate that I could perform at a collegiate level.”

He enrolled in Fisher Junior College and took a semester of English, Algebra and Business Law classes. When he presented the results to the Admissions Office they accepted him as a conditional student.

“Receiving the acceptance letter was life changing and brought me to tears,” he says. “When I got to the campus it was a bit overwhelming. A lot of self advocacy was required. There were no dorms . . . I didn’t know a soul at the time, and so it was a bit intimidating, but it was an effort I knew I had to make, so I just kept pushing myself.”

“UMass Boston was a universe away from where I was, both socially and intellectually. By the age of twenty-nine (my graduation) I was an entirely different person from when I started.”

It was a commuter school with an older population that suited Rooney’s determination to take the most out of college that he could.

“I took it very seriously,” he says. “I didn’t party, didn’t go to bars, didn’t smoke or drink. I took it very seriously, and what I came to realize was that anything that you want to do in life is just right there, right next to you, and that all you have to do is to go out and just get it, and that was a prospect that was not open to me until I went there and started to engage in these small victories.”

He took several work-study jobs and started working as counter help in the Financial Aid Office in his sophomore year. He served as the first-line interaction with students attempting to resolve financial aid issues. He began writing a brief column for the Mass Media about scholarships available for students. This introduced him to the Student Activities area of the university and the Student Senate.

“I wanted to start a competing student newspaper,” he says. “I petitioned the Student Senate for funding and was ultimately denied. However, during that process the Senate offered me a proposal to revive the failing campus literary magazine, Howth Castle.”

He took on the project of resuscitating the campus arts journal and recruited a team. That’s how he met Beth Pratt and Matt Duggan.

“I was provided with funding for one year to succeed or fail,” he says. “If I did not accept, the magazine would be ended and the annual line item funding would be returned to the Student Activities Trust Fund for allocation to other groups . . . as far as Beth and Matt, we’re still friends.”

In the late eighties UMass confronted the economic realities of the of the so called “Mass Miracle,” when the biotech boom entered recession. This brought tremendous financial burdens on the state, and Governor Michael Dukakis wanted to slash the UMass budget. “Budget cutting by the state government was swift and brutal,” Rooney says.

He joined an advocacy group called the State Student Association of Massachusetts (SSAM), and soon found himself serving on the statewide executive committee, nominated to serve as the Legislative Chair.

“We crafted several legislative bills that became law during that time,” he says. “During the financial turmoil, my role in statewide politics became more visible and my work with the Student Senate more common. I met the then-Student Trustee Alex Walker who asked me to testify at the State House in front of the Massachusetts Legislature in support of UMass Boston.”

Rooney describes the testimony he gave in the Gardiner Auditorium as one of the highlights of his college experience.

“The forum was a large open room with the legislatures up high above you, looking down upon you like some Roman effect, and at the table, myself and other people from the academic community, all waiting our turns to tell these legislators, these people who controlled our future, why we needed what we needed . . . I recall even to this day sitting there thinking that I cannot believe that I am here doing this.”

Soon after that, Alex Walker asked Rooney to run for the Office of Student Trustee and be his successor. Elected to the Board of the Trustees as Student Trustee in the 1989/90 academic year, Rooney became an outspoken advocate for education funding.

“Great political forces were pressing against the university from both the legislative and executive branches. It is with this backdrop that I and other student trustees across the state began a campaign of support for higher education in Massachusetts.

He worked with student trustees from Dartmouth and Amherst, and politically active students from state colleges all over the state.

“We had all the schools go back to their student senates and appropriate funds for busses, and there were school strikes out in Amherst.”

The student advocacy groups of SSAM, the Student Trustees, and other student groups all across the state were mobilizing, culminating with a massive rally at the State House where more than 20,000 students bussed in from all across the state, protesting the budget cuts to our campuses.

“Our collective efforts successfully forced candidates in the Governor’s race to make higher education funding one of the top three platform points of every candidate’s campaign. If you weren’t talking about higher education, if you didn’t have a plan, you were not a credible candidate for Governor in 1990.”

Rooney was on the front lines of the protests, hyperactively testifying to legislative committees, appearing on local television news programs and protesting on the campuses and the streets of Boston.

Meanwhile, the Boards of Trustees across the Commonwealth were working with the Massachusetts Board of Regents and the legislature to reorganize the entire higher education system into the system we now have today. This unified voters from the “four points of the compass” to act as one group to defend the interests of higher education in Massachusetts.

“Ultimately, we were successful in fending off the horrific budgets cuts, the scale of which would have devastated the Boston campus and would have forced the closing of entire colleges on the campus, such as the Schools of Education and Nursing.”

After graduating, Rooney moved to Martha’s Vineyard to work on a wooden boat building project. There he met his wife, married and had a daughter together.

Later he worked for the Martha’s Vineyard Commission as transportation planner, coordinating with the six island towns.

Today he owns a brokerage and studies the historic titles to properties on Martha’s Vineyard, particularly in the Town of Aquinnah, which is the native land of the Wampanoag Tribe.

“At first gloss, for the uninitiated, it sounds rather flimsy, the mission, but looking back with the benefit of 25 years hindsight, and seeing what we had to do to protect the mission, I now understand more about the mission, and the mission is to provide opportunity to people like me, because I could never have afforded to go to any other university. UMass was the inexpensive alternative.”

Buses Brought Thousands of Protesters With Richard Rooney to the State House in 1990

By Caleb Nelson

|

November 5, 2015

About the Writer

Caleb Nelson served as the following positions for The Mass Media the following years:

Editor-in-Chief: Fall 2010; 2010-2011; Fall 2011

News Editor: Spring 2009; 2009-2010