WUMB began as a notice on a giant bulletin board in the lobby of the main campus building at 100 Arlington Street in Park Square, where students posted advertisements for groups, meet-ups, hangouts, and hookups.

“I remember seeing a sign on the bulletin board that said there was a bunch of students looking to start a radio station, and for some reason that fascinated me, and I went up to the meeting, and the rest is history.”

About 25 students gathered on Halloween, October 31st, 1968 to figure out how to start a radio station. Monteith still has the sign up sheet. She wrote there that she was interested in talk programs.

“There was a lot of passion in the room. Even from that very first day the interest was to do something that did not exist on the radio dial at that point. We weren’t quite certain what we wanted to do, but we knew that what existed on the radio dial wasn’t something that satisfied us.”

They formed a committee, and went around to the many local stations looking for advice.

“I remember seeing a sign on the bulletin board that said there was a bunch of students looking to start a radio station, and for some reason that fascinated me, and I went up to the meeting, and the rest is history.”

About 25 students gathered on Halloween, October 31st, 1968 to figure out how to start a radio station. Monteith still has the sign up sheet. She wrote there that she was interested in talk programs.

“There was a lot of passion in the room. Even from that very first day the interest was to do something that did not exist on the radio dial at that point. We weren’t quite certain what we wanted to do, but we knew that what existed on the radio dial wasn’t something that satisfied us.”

They formed a committee, and went around to the many local stations looking for advice.

“Everybody laughed at us because they said the radio dial in Boston is closed down. You’ll never put another radio station on the air, and so we were discouraged, and for a while and we let that be.”

Disheartened, they put together a closed circuit radio station in the basement cafeteria of the Sawyer building in the downtown campus. Bose donated equipment.

“Every single morning we would climb up and stand on the tables, throw chains over the pipes, and hookup four 901 speakers, which were connected to an amp that we got from another local company, and we played radio. We basically replaced the jukebox in the cafeteria.”

Student DJs brought their own records, and played their music all day long.

“If we played something the students didn’t like, they would throw food at the window. That’s called instantaneous response. It was fun. It was also scary sometimes.”

Disheartened, they put together a closed circuit radio station in the basement cafeteria of the Sawyer building in the downtown campus. Bose donated equipment.

“Every single morning we would climb up and stand on the tables, throw chains over the pipes, and hookup four 901 speakers, which were connected to an amp that we got from another local company, and we played radio. We basically replaced the jukebox in the cafeteria.”

Student DJs brought their own records, and played their music all day long.

“If we played something the students didn’t like, they would throw food at the window. That’s called instantaneous response. It was fun. It was also scary sometimes.”

After a few semesters of daytime DJing, members of the burgeoning WUMB made a deal with WBCN, located just across the street, to get the news off of their Associated Press wire service. One of the DJs that they knew there suggested that they contact record companies for music.

“Somehow I got assigned the responsibility to do it, and that made a huge change in the operation. It made a huge change with me too. It opened me up, being a very shy person, to naturally talking with people, or negotiating with people, and we ended up getting record service from just about every record company in town.”

As a math major, Monteith first became the radio committee treasurer and book keeper. As the newest music releases arrived regularly at student activities, the student radio station rooted into campus life, and because she got the records, Monteith became the Music Director.

“Even from the beginning we had a lot of support from the faculty and staff on campus,” she says. “There was a physics professor by the name of Hal Mahon, and it was great because he knew how to get things done. He knew the right people to talk with, and kept sending us in that direction. We became friends with the folks in facilities. The chancellors and vice chancellors were very supportive, so it really didn’t take a lot of convincing.”

After graduation, Monteith continued working at the radio station while studying at Emerson, where she got a master’s degree in Communications. Meanwhile, she convinced facilities to pull wires through the brand new campus on Columbia Point, which opened in 1974. The wires ran from a studio in the basement of the Healey Library throughout the campus, into the cafeterias, student activities, and a few of the hallways.

“Somehow I got assigned the responsibility to do it, and that made a huge change in the operation. It made a huge change with me too. It opened me up, being a very shy person, to naturally talking with people, or negotiating with people, and we ended up getting record service from just about every record company in town.”

As a math major, Monteith first became the radio committee treasurer and book keeper. As the newest music releases arrived regularly at student activities, the student radio station rooted into campus life, and because she got the records, Monteith became the Music Director.

“Even from the beginning we had a lot of support from the faculty and staff on campus,” she says. “There was a physics professor by the name of Hal Mahon, and it was great because he knew how to get things done. He knew the right people to talk with, and kept sending us in that direction. We became friends with the folks in facilities. The chancellors and vice chancellors were very supportive, so it really didn’t take a lot of convincing.”

After graduation, Monteith continued working at the radio station while studying at Emerson, where she got a master’s degree in Communications. Meanwhile, she convinced facilities to pull wires through the brand new campus on Columbia Point, which opened in 1974. The wires ran from a studio in the basement of the Healey Library throughout the campus, into the cafeterias, student activities, and a few of the hallways.

“If you wanted something, and you convinced people that you really wanted something, everybody rallied around you. Whenever I came up with an idea, no matter how crazy it was, there were faculty and staff to rally around it and try to make it happen.”

She worked at WUMB for $35/week, overseeing the station as it transitioned onto the harbor campus. She kept working on the application for their FM license, which took 14 years to process. The FCC finally put WUMB on the air in 1982.

“Even in the beginning, back in ’68, we had three or four folk shows. Folk was part of the counter culture back then, not only in the Cambridge area in particular, but also across the country.”

“We were influenced by everything that happened at Kent State [the campus shootings in 1969]. I remember that day so vividly. We were in class. They ended up letting school out because it had such an impact on everybody in the institution, and I remember walking down Arlington Street with a bunch of students and we didn’t know how to react.”

WUMB became one of the nation’s biggest and best folk stations, now online @wumb.org and 91.9 in Boston and eastern Massachusetts on the FM dial. After 44 years of working to build the station, Monteith found a new outlet for her creativity through mentoring kids.

“That campus opened so many doors for me in so many ways and people were so helpful. If you had an idea, people wanted to help you succeed with it, and that stuck with me. You just don’t find that. Most people want to squelch ideas. The faculty there [at UMass Boston] and the staff there were so supportive.”

She worked at WUMB for $35/week, overseeing the station as it transitioned onto the harbor campus. She kept working on the application for their FM license, which took 14 years to process. The FCC finally put WUMB on the air in 1982.

“Even in the beginning, back in ’68, we had three or four folk shows. Folk was part of the counter culture back then, not only in the Cambridge area in particular, but also across the country.”

“We were influenced by everything that happened at Kent State [the campus shootings in 1969]. I remember that day so vividly. We were in class. They ended up letting school out because it had such an impact on everybody in the institution, and I remember walking down Arlington Street with a bunch of students and we didn’t know how to react.”

WUMB became one of the nation’s biggest and best folk stations, now online @wumb.org and 91.9 in Boston and eastern Massachusetts on the FM dial. After 44 years of working to build the station, Monteith found a new outlet for her creativity through mentoring kids.

“That campus opened so many doors for me in so many ways and people were so helpful. If you had an idea, people wanted to help you succeed with it, and that stuck with me. You just don’t find that. Most people want to squelch ideas. The faculty there [at UMass Boston] and the staff there were so supportive.”

Shortly before she left the campus in 2012, Monteith heard an interview on the station’s Commonwealth Journal program with Jean Rhodes about the importance of mentoring urban youth in particular, and how much of a difference mentorship makes.

“I’ve had a lifelong interest in science, and been involved in volunteering for local science fairs, and so I went to the president of the Boston NAACP, and I said hey I’d love to help re-establish their program.”

“I started working with mentoring some of the science students for a local competition, and eventually a national competition, and it was the single most rewarding experience that I’ve had pretty much in my life. Absolutely amazing to see how the students that I worked with developed, and grew, and gained trust in me, and the whole idea of success, and so now I’ve sort of developed that in a lot of other areas.”

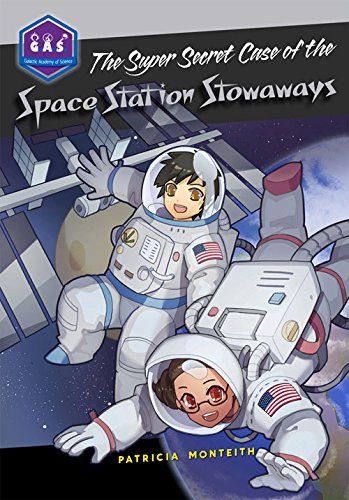

When Monteith started college, her dream was to work in mission control for NASA. Now she’s in the final stages of writing a children’s book about the International Space Station, “The Secret Case of the Space Station Stowaways,” which is coming out in April through Tumblehome Learning.

Monteith enjoyed every year that she got to serve as WUMB’s Program Director, and she’s thrilled to see the new structures popping up on campus.

“I always kept saying this place is a diamond in the rough. One of these days it’s finally going to get its due, and that’s happening now. It’s wonderful to see success, and the success needs to continue, and it needs to no longer be a diamond in the rough. It needs to be thought of as the jewel of Massachusetts.”

“I’ve had a lifelong interest in science, and been involved in volunteering for local science fairs, and so I went to the president of the Boston NAACP, and I said hey I’d love to help re-establish their program.”

“I started working with mentoring some of the science students for a local competition, and eventually a national competition, and it was the single most rewarding experience that I’ve had pretty much in my life. Absolutely amazing to see how the students that I worked with developed, and grew, and gained trust in me, and the whole idea of success, and so now I’ve sort of developed that in a lot of other areas.”

When Monteith started college, her dream was to work in mission control for NASA. Now she’s in the final stages of writing a children’s book about the International Space Station, “The Secret Case of the Space Station Stowaways,” which is coming out in April through Tumblehome Learning.

Monteith enjoyed every year that she got to serve as WUMB’s Program Director, and she’s thrilled to see the new structures popping up on campus.

“I always kept saying this place is a diamond in the rough. One of these days it’s finally going to get its due, and that’s happening now. It’s wonderful to see success, and the success needs to continue, and it needs to no longer be a diamond in the rough. It needs to be thought of as the jewel of Massachusetts.”

Math, 1973