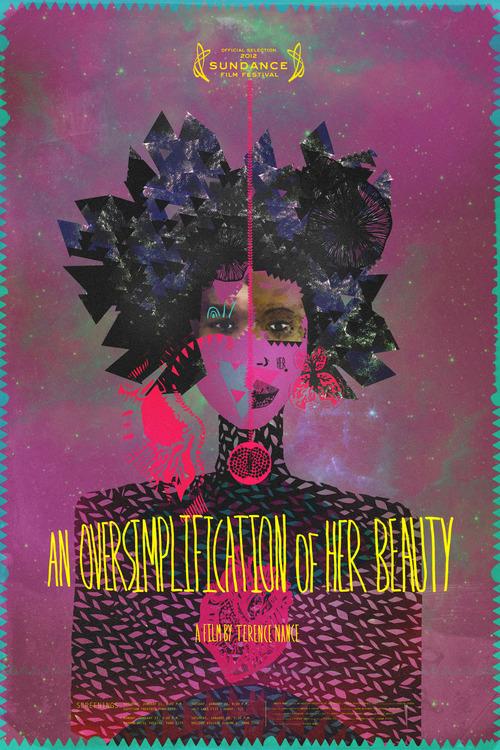

In January of this year, the experimental documentary “An Oversimplification of Her Beauty” premiered in the New Frontier section of the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. The film’s maker, Terrence Nance, immediately went online to Kickstarter to raise funds in order to polish the rough cut of the movie and take it cross-country to the festival. Each one of the sixty people who donated over $100 got a piece of Nance’s original, hand-drawn animation from the film.

“An Oversimplification of Her Beauty” stayed in Utah at the Salt Lake Art Center until May 19, when Nance took it on the road. It’s been shown in film festivals in San Francisco, Los Angeles, New Orleans and New York. On November 15, 2012, the movie appeared at UMass Boston as part of the UMass Boston Film Series, presented by local documentarian and UMass professor Chico Colvard. Nance was present for a Q&A session after the film.

The film is actually a combination of two films. One, “How Would You Feel?,” Nance made for a class and presented to the public in 2001. “How Would You Feel?” describes the filmmaker’s complicated almost-relationship with a woman named Namik Minter. The other, “An Oversimplification of Her Beauty,” is a critique of and commentary on the first, finished many years later after Nance and Minter had stopped speaking.

The subject matter of Nance’s work is not unusual; he depicts the lives of young black adults living in Brooklyn, focusing on one heartbroken male protagonist. He explores his own history, his past breakups, and the personal faults which might have led to Minter rejecting him. “An Oversimplification of Her Beauty” also references the poverty Nance experienced as a student. The film supplies b-roll footage of him carrying pieces of a bed frame back and forth on the subway as he attempts to build his own furniture and also of him playing guitar in public places for change.

What is not typical is Nance’s approach. The movie is one of a few that depicts the lives of young, educated black people without explicitly mentioning their color. There is no direct discussion of racism or race or white people in the film. What exists instead is a day-to-day existence in which he not only refers to himself as chronically late by saying “my punctuality is Afrocentric,” but strangers on the train feel entitled to touch Nance’s “exotic” hair.

His stylistic choices are also unusual. The two documentaries pile on top of each other with indistinguishable plots and styles. The movie begins like many others, with video of a central character (Nance) going about his life, and slowly introduces animated interludes drawn by Nance himself. By the end, almost all screen time is devoted to animation. The entire film is narrated in the third person by an anonymous broadcast voice of a man much older than Nance.

It is in these seemingly odd stylistic choices that the documentary is most successful. Nance’s romantic autobiography, an unwieldy hybrid of b-roll and animation, is both unique and extraordinarily beautiful.