The University of Massachusetts Boston prides itself on being at the forefront of environmental research, restoration, and protection. However, our efforts in one area have been led astray due to misinformation.

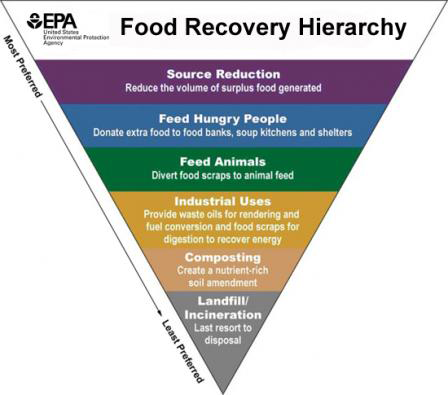

Composting has been considered the “pinnacle” of recycling and has been hailed as the “the greenest thing you can do” by the environmental publishing platform One Green Planet. This is in spite of the United States Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) ranking of landfilling as the worst use of food scraps on its Food Recovery Hierarchy.

The most preferred way to deal with food waste is to prevent it from existing. The first step to reach this goal is to conduct a waste audit, which is a fancy way of saying we should check where the food waste is coming from. Since 2014, the EPA has offered a free 26-page guide on how to perform a food audit. This includes instruction for planning the audit and making accurate measurements.

Responding to the information gained in this guide is fairly straightforward. If students throw out leftovers, then offer smaller meal sizes. If students throw out whole meals, then offer taste testing so they only buy what they know they will eat. If food has been spoiling, then give the staff a review course in proper food storage and preparation techniques.

Based on a five-day food audit, the University of Texas at Austin managed to use these strategies to cut its wasted food by 48 percent.

The next level on the EPA hierarchy is so obvious that most people overlook it—donations to people. Food banks will thankfully accept any prepared food that has not been sold or includes ingredients nearing their expiration date. The fear that donating food creates an unneeded liability on the part of the donator is unfounded. The Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act removes the liability of foodborne illnesses from a donor as long as the donor has not acted with negligence or misconduct.

Providing food to animals is the EPA’s third preferred choice, and it mirrors the prior tier perfectly, except that food banks are replaced by zoos and farmers.

Rutgers University in New Jersey has been running a food waste diversion program for so long that the original farmers collected the food waste in a horse and buggy. Rutgers currently produces 1.125 tons of food waste per day and pays half as much to the farmers than they would to send the scraps to a landfill.

The last tier before composting, and perhaps the most interesting, is the using of food waste as raw material for industrial processes. Fats, oils, greases, and meat can be given to the rendering industry, who can turn them into everything from toothpaste to explosives, or can be processed into biodiesel, which is a non-toxic replacement to diesel that does not produce nearly as much soot or sulfur dioxide, one of the chemicals responsible for acid rain.

While rendering and biodiesel production can only be done with some types of food waste, any type can be sent to an anaerobic digester, which produces fertilizer and methane gas, unlike composting which only results in fertilizer.

Even though methane generated this way is chemically identical to natural gas, and is therefore compatible with existing infrastructure, it is a renewable resource and is much better for the environment because it does not create any of the pollution associated with mining.

The EPA has praised the University of Wisconsin Oshkosh for creating the first dry fermentation anaerobic digester in the country and using the gas it produces to meet 10 percent of its power demands.

Is it too much to request that UMass Boston send its food waste to the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority’s Sewage Treatment Plant on Deer Island, a move that would help UMass Boston reach its goal of using 100 percent renewable energy? Are any of these suggested strategies too burdensome for our great university?