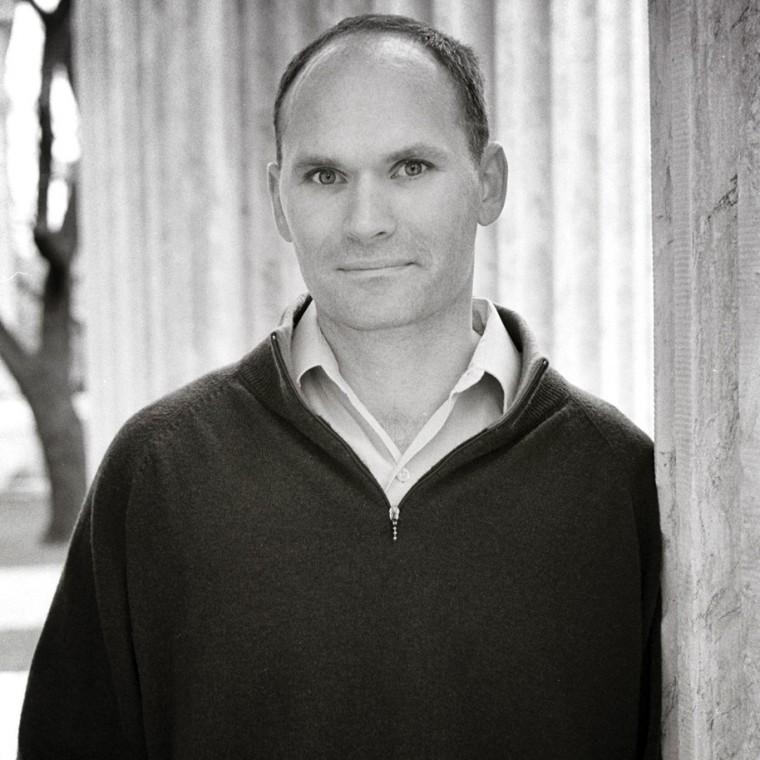

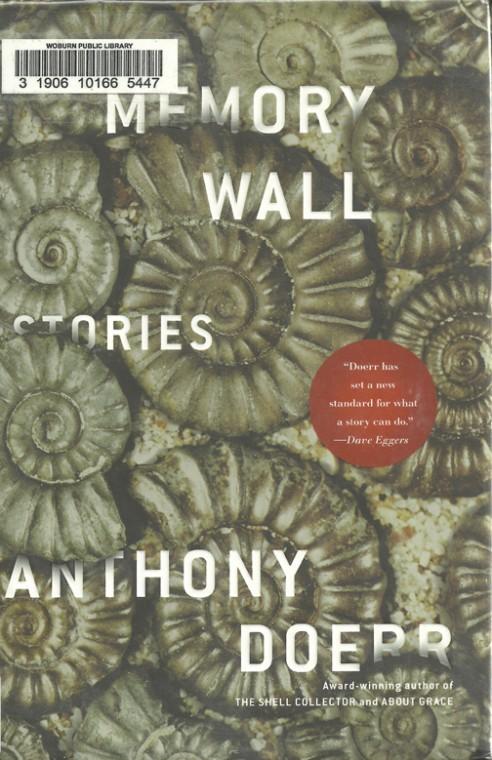

Nobody reads short fiction anymore, unless they’re in a nursing home, in jail or otherwise isolated enough to find National Public Radio amusing. The days of Jack London, Agatha Christie and Ernest Hemmingway have ended; the days of Dr. Dre, Steven Spielberg and Tina Fey have come. We’re living in the decade of the touchscreen, but fiction didn’t die. It’s just hiding out behind the bright lights, in the tireless effort of authors like Anthony Doerr.

Recently I got to speak with Anthony Doerr over the phone for a fiction class. The anticipation got me discombobulated, and I forgot to erase my recorder. I hooked it up to the phone, but it only recorded eight minutes of our conversation. Most of the following interview has been reconstructed from my notes.

Do you have someone in mind when you sit down to write a short story?

You know, I’ve heard writers say that they will think of a specific person. I don’t think of myself as a selfish person, I am trying to write the kind of books that I would like to read. So I don’t picture, like, a Finnish woman on a bus, reading on her way home from work, although I do like that idea.

Do you have a whole story in mind before you start writing?

Rarely. Rarely. Never do I have all the solutions in place for where something is going to go, and I kind of like that. I think I’ve become comfortable being in that slightly frightening place, where you don’t fully understand where something’s going to end up. You’re kind of fumbling down dark hallways and making the hallways as you go, and that means a lot of the times you have to backtrack and erase 20, 30, 40 pages because you realize, “Oh crap, they don’t need to be in this situation.” But you get this thrill of surprise when you put characters into situations. You still don’t fully understand who the characters are, but if your day’s going well you surprise yourself.

Where do you begin a short story?

I start with an idea or point of interest, and write until I hit a wall. You know, sometimes you come up with an idea and start working on it and realize that you need to change direction, or put some action earlier, or change the gender of a character. It’s a gradual process and a lot of blood and sweat before you really hit on something.

What’s your rewriting process like?

All writing is revision. Often I start the day by reading over what I have written and build on it. I’m rarely generating new ideas when I’m really writing. Generally I’m repairing, altering and streamlining. The ideas are more the sort of things that you get out of the shower and think of and you write them on scraps of paper. Then later you sit down and start to develop them.

What do you think about as you’re working on your sentences?

I think I’m influenced by what I’m reading while I’m working on a piece. So if I’m reading Faulkner I’ll drift into more flowery sentences, or when I’m reading Fitzgerald or Kramer I’ll write more crisp sentences. There’s no real secret to writing a sentence. You get a feel for it, like when you’re listening to music. As you’re reading, you get a feeling for the tempo and tone.

Do you read any of your past stories now?

I would never, ever go back to those stories on purpose. Sometimes I get asked to read some of my older stuff and I’ll oblige. But I suffer through it. As a writer, when you have a successful book immediately you get kind of self-conscious. You want to believe you’re getting better and you live in fear that your best work is behind you. I think there’s this pressure that I feel to do better, and I do feel like I am better. When I’m doing readings, I focus on my newest material. It’s very rare for me to go back and read anything that I wrote when I was younger.

When was the last time you read a story from “The Shell Collector?”

I was invited to a country club by a group of older ladies for a reading. That was something else. Imagine that life, just hanging out on the edge of the pool, enjoying the pool and a three-hour lunch. They had a book club and they really wanted me to read from “The Hunter’s Wife.” I read about three pages, and I felt like I dwelled a little too much on the language when I was writing that story. It wasn’t very fun for me to read.

In some ways first books are really pure to read. You’re not thinking, “I hope that the reviewers notice this one,” or worried about making an impact with it. You’re coming from a pure place as a writer with your first book. I think it would be an excellent exercise to spend a year just reading first books. There are often these little clunky moments, but there’s something dreamy-like and really innocent about the writing in a first book.

This full interview will be published in the spring edition of “The Watermark,” UMB’s student-run literary journal. In conclusion, I’d like to suggest some old-fashioned entertainment. Read Anthony Doerr, even though you can’t find his work on Hulu. It’s all available as eBooks.