In the span of three weeks, I’ve trekked through deserts and mountains, met nomadic minorities, and traveled one of history’s most famous trading routes. Returning to Beijing seems anticlimactic in comparison. Words seem so limiting when you’re trying to translate a psychological, cultural, and physical experience into a few paragraphs that a reader can understand.

The average person can expect to live to sometime into their 70s-barring natural selection and human stupidity, a small but significant factor. Through all these years, we have memorable experiences that affect us in some way. But do we ever know how much or how little they impact us? It’s rare to even realize that they have. Yet, I know that this voyage has changed my perceptions of myself, my heritage, and any ideas I had about China itself. It’s not enough to read about a situation or hear firsthand traveler’s tales. To feel it, you must experience it.

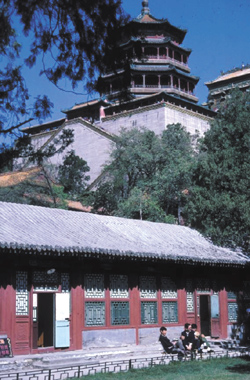

So, while I wasn’t as excited to see Beijing as I was when I first set foot on Chinese soil, I was glad to be back. For the remainder of our trip, we went to see some of the tombs of the Ming dynasty emperors.

Before the capital became Beijing (in the Ming era), it was located in Nanking. The first emperor of this era established himself by defeating the Mongolian hordes that had occupied northern and northeastern China for some time. With the help of his brother, he drove them back and, in reward for his services, made his brother king of Beijing while he remained down in Nanking. However, that wasn’t enough for his sibling. The emperor designated his second son to be his successor. This enraged his uncle and, upon the death of his brother, he usurped the throne and moved the capital to Beijing where his power base was centered.

This is where history becomes a little cloudy. His uncle, furious that his nephew had escaped, demanded that his head be brought before him, as proof of his death. His uncle murdered most of his 40 other brothers and sisters, so there wasn’t much else to worry about. Supposedly, the 17-year-old prince headed south towards Malaysia and Indonesia and married one of the Indonesian locals. My father told me that, on one of his frequent trips to Malaysia, he was told that a tomb in Penang was actually that of the errant heir. They don’t have the money to verify and research it but local lore tells of a nobleman seeking and taking refuge somewhere in the waters of Southeast Asia.

I love a good story as much as anyone else but I wonder how much of this is based in fact or fiction. It drives the imagination. Many archaeological discoveries are purely accidental. A would-be explorer overhears the natives discussing or referring to ancient places in passing and wants to know more, hoping to stumble onto the Cibola that Coronado never found. Anyhow, the now-Emperor reigned for 20 years before dying and passing on the power to his own offspring.

It is his tomb we saw, buried deep in the side of a mountain. You spend a good hour hiking up the trails that lead to the top of the man-made peak, only to walk down flights and flights of stairs to the bottom of an almost-empty shaft. Most of the artifacts are housed in a surface level museum. Going to the floor of the cavern where the coffins are is just to give one an idea of how much work went into producing a testament to one man’s greatness. Ego knows no bounds: just look at the pyramids.

Only three of the tombs are open out of the thirteen that reside in Beijing. Again, the lack of money available for preservation is a hindrance to any of these other burial sites being opened to the public. Monumental amounts of money, pardon the pun, are required for just trying to keep places like this open. Most of them run on a skeletal crew and budget, especially noticeable in how little security there is sometimes.

One thing I found that was rather random was a lone ornate archway standing at the foot of the tomb’s entrance. I went through it, thinking that there had been a fence at one time. There wasn’t. It was symbolic in that, in passing through, one was making a transition into death. If you should happen to go in, then you make damn sure you better go out. This has more to do with luck and taboo than anything else.

We pass off a number of things to superstition and blame it on lack of knowledge. Yet, it is just as ignorant to assume we know best, as it is to blindly believe in random rules without knowing the reason why. Although there was no logical or rational basis to step back through,

Beijing looked more modern than I first thought when I arrived. The perspective I gained in the desert and mountain areas has made me realize that, with open sewers and poverty as well, it is a cosmopolitan city compared to the sparsely dotted plains of western China. We spent two more days going around and mostly shopping for family and friends, but our minds were filled with a longing for home.

Chinese history is a better read than most modern thrillers. Take the political intrigue of Queen Elizabeth’s court, add Days of Our Lives plot swings and occasionally Jerry Springer-esque family members, Yoda-like logic, top it off with Yankees-Red Sox type power struggles, and voila!, you’ve got the first few dynasties covered. Some of these tales made good bedtime stories when I was a child. It is quite different to see the truth of it up close with unequal amounts of tragedy and triumph, a portrait true to the ever-shifting tides of life.

My father told me that, in all actuality, this is probably the last time we would travel together. He assumes, maybe rightfully, that I will be busy with school, a career, and a family. Time passes more quickly than most of us realize. He wanted this to be memorable and he wanted to teach me something. He has accomplished his goals.

As the humidity causes my cloths to stick to me in the room of my Andrew Square apartment, I can only wonder when we will ever be able to go back and again wander those roads that history forgot.