The right to protest — a freedom granted under the first amendment of the United States Constitution — has once again become a hot topic at universities all over the nation. The encampments in protest of the war in Gaza caused a stir last year, pushing universities everywhere to change their policies regarding protest to be more strict and specific.

Where did it all start? The protests at University of California Berkeley in the 1960s kicked off a lot of the student movements seen today. At this time, the students were fighting censorship of political activities, especially those regarding the Civil Rights movement.

The same issues are still being fought for today — and as far as the record goes back — at UMass Boston.

The efforts to bust protests and student speech goes back to the very design of the campus buildings. In a 1998 interview done by Johanna Duponte with founding member of the university Dr. Duncan Nelson, he explicitly states the intention of the campus design to make protests more difficult as a result of the Vietnam War.

When faced with preexisting safeguards to prevent such demonstrations, activists had to turn to more creative outlets. Students would create pamphlets and flyers with political cartoons and slogans. They wrote stories and poetry in the literary magazines that came and went. From its first issue on Nov. 16, 1966, The Mass Media was a widely used source for student voices.

“At this particular time, the word, ‘protest’, and the subject which it implies, has become one of the most controversial, misunderstood, and even hated words in common usage,” wrote The Mass Media Editorial Board in their first ever print, in an editorial called “Protest – It’s an Adult’s Democracy.” The authors criticize reactions from older generations to the movements of the time.

The Mass Media amplified student voices by allowing contributors to write and voice opinions. They also created “opinion ballots” regarding current events that could be filled out and dropped off in a box for results to be printed in a later issue.

When writing wasn’t enough, students escalated as far as holding a sit-in outside the office of former Chancellor Robert Corrigan. The sit-in was a response to a new policy regarding tenure-track faculty that students deemed problematic. 25 students — in a planned demonstration — demanded to meet with then UMass President David Knapp and were dismissed with a letter of support for Corrigan.

“Initially denied access to the twelfth floor, where Knapp’s office is located, the students roamed the stairwells until they found an open entrance to that floor. They seated themselves in the waiting room outside Knapp’s office and refused to leave until they recieved a definite appointment with the president,” The Mass Media reported on the event.

Knapp and Corrigan finally agreed to meet with five student representatives, only to deny every single one of their demands. This caused a second sit-in of over 50 people in the waiting room of Corrigan’s office, which lasted a week before students were arrested and charged with trespassing.

Protest at UMass Boston has not been restricted to students — campus unions have been fighting long and hard for many of the same issues for decades. Photos from the 1990s show union members lining hallways in Quinn Administration Building holding signs with issues that are still repeated today.

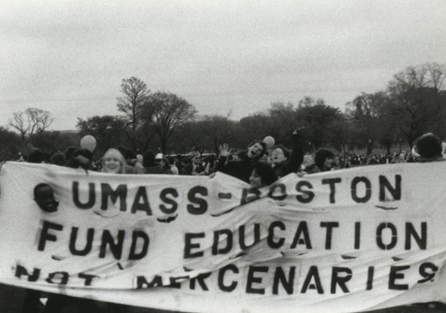

Students, faculty and staff, including over 200 from UMass Boston, came together across different Massachusetts colleges and universities to march at the state house in 1991. The protest, often called the Education Rally, was against sitting Governor Bill Weld’s decision to cut the public higher education budget.

The concept of protesting has shaped UMass Boston into the public university it is today. From the design of the campus to its student media, activism is ingrained in the university culture and anti-racist values that UMass Boston hopes to reflect. Protecting free speech and on-campus demonstrations represents what it truly means for UMass Boston to be “for the times.”