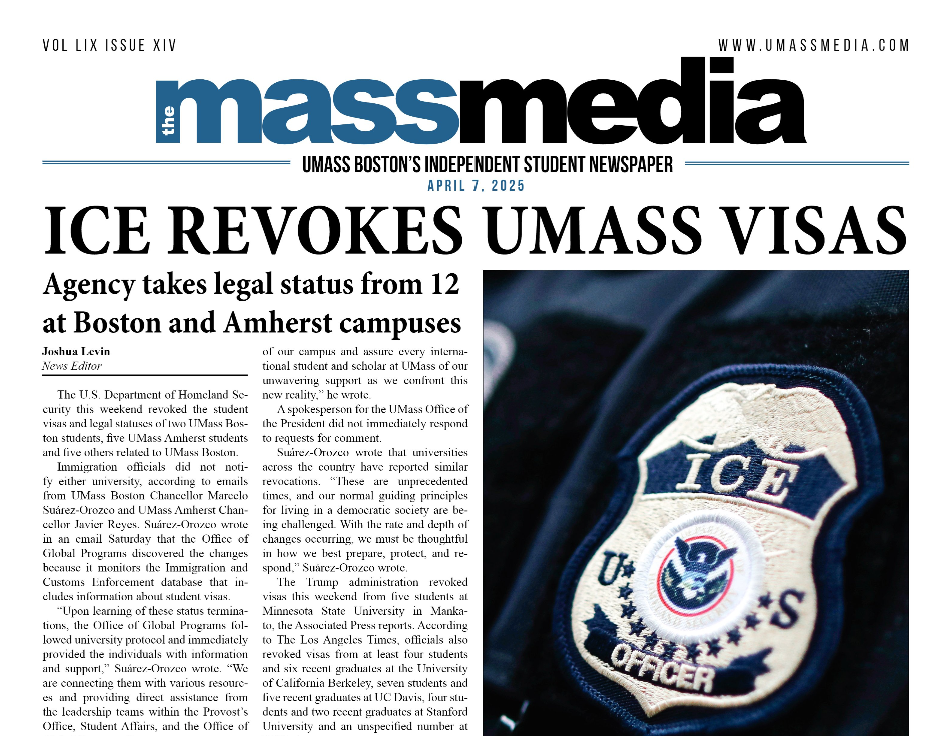

Everyone Is My Family

February 5, 2002

Philip Nerboso found the inspiration for his American Studies 100 Project in a heap of old T-shirts at a thrift store. The shirt holds a brightly colored self-portrait by a six-year-old girl which boldly proclaims, “Everyone Is My Family.” Instead of the more traditional family portrait we are used to seeing at the hands of a kindergartener, this mystery girl expanded on the ordinary line-up of family in front of a smoke-coughing cabin of a house, starting with dad as tallest and going down the line to mom, brother, sister, and finally, dog and/or cat as shortest. She put only herself, with open arms on a mat of scraggly grass, and scrawled an invitation to any and all as members of her family.

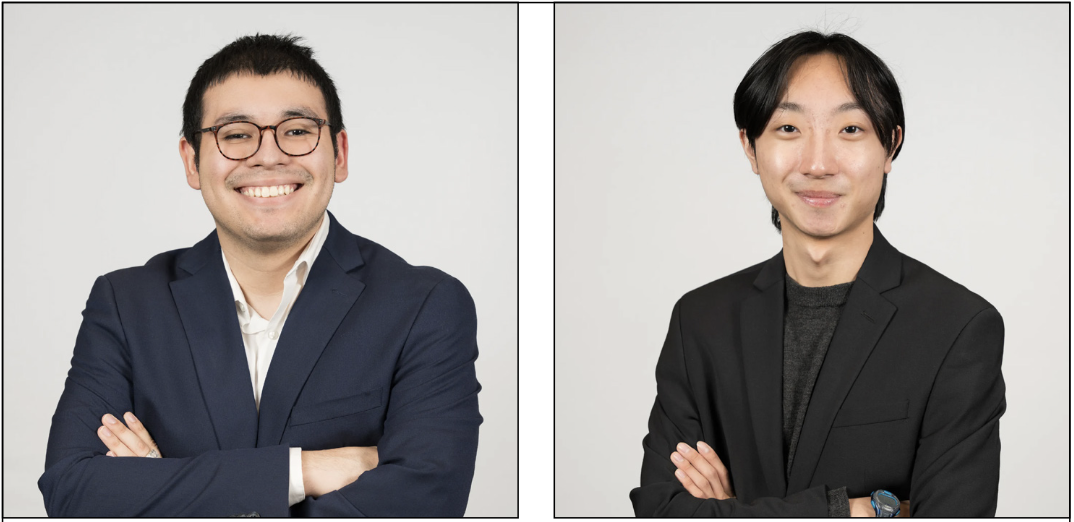

Nerboso, an Art major at UMB, comes from a very non-traditional family. His mother remarried three times during his childhood. He has a scattering of step brothers, half-brothers, and half-sisters due to this constant familial rearrangement. He has had a handful of people in his life refer to him as Brother Phil, as a term of endearment, even though they weren’t related to him. He also treats some of his closest friends as others may treat their biological family members.

So when he received the assignment from American Studies Professor Shirley Tang to write a 15-page paper going back at least three generations and paralleling historical events with significant family events, Nerboso foresaw himself having some difficulty with this assignment. Should he chronicle only biological family? Did his extended family count? One of his stepfathers had adopted him, could that lineage also be considered?

He decided to use this opportunity to advertise the idea he shared with that mysterious young girl who had produced the T-shirt. He arranged with his professor to produce an artistic representation of the idea “Everyone Is My Family” along with a shorter written paper. Professor Tang agreed.

The result can be seen on the walls of a Wheatley Hall stairwell between the fourth and fifth floors. Nerboso scanned images of people’s faces, trying to represent all ethnic groups.

“I failed though,” he said, “I realized there were no Inuits.” But he later added that it was okay because “the point was not to show everyone but to give the impression of everyone … with different skin types and faces.”

He scanned the images he had chosen to fit the size of the hallway’s bricks. At the center, the only image in color is the little girl’s drawing. Surrounding her bright hues are black-and-white portraits of varied faces. The faces are not in any particular order. After he placed them on the wall, Nerboso took a single red thread and sewed through all the images. He took the thread straight across, diagonal, up and down, creating a web between the many faces staring out at you from the bricks. Then he let the needle fall between the many threads, where it still hangs as though someone could pick it up and continue the connection.

When it was first displayed, the piece also had an audio component. Nerboso secretly recorded his extended family at a recent function, a holiday celebration. He played the tape of those many voices from the sixth floor of the stairwell, so it would be muffled and unintelligible. The audio part of the installation is no longer playing, but you can imagine the voices as you look into the black-and-white faces staring out from the wall.

“The point of the project is to expand upon the notion of what people typically think of as family and what it would mean if everyone thought of everyone else as their family,” said Nerboso.