Voices From Colombia

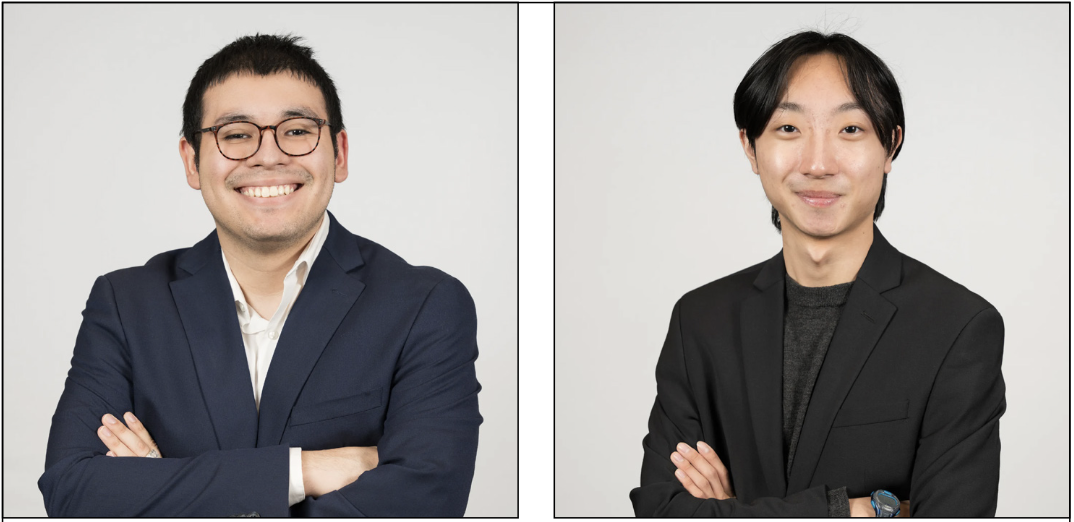

A representative from CPCS (standing) introduces speakers (seated left to right) Eder Jair Sanchez, Hector Giraldo, and Carolina Aldana at a recent talk on Colombia.

October 16, 2002

Imagine you are a peasant farmer in Colombia, you grow plantains, and yucca root. The food crops you grow are not enough to earn a livable wage, so in addition you grow coca plants for export. This is a cash crop, it brings income … and danger. One day, you look up to see planes dusting your crops with herbicide, even your food crops.

According to a recent forum sponsored by the College of Public and Community Service, which addressed the current situation in Colombia, scenarios like the one above are not so far-fetched.

In the past few years, the United States policy in Colombia has centered around something called “Plan Colombia,” part of the war on drugs. In the summer of 2001, the Bush administration was beginning to review their Colombia policy. But, after the events of September 11, attitudes toward Colombia began to tighten, with slight revisions in the policy which, if approved, will allow for US dollars to be used for a wider range of counter-drug and counter-terror efforts. In the past, at least on paper, the foreign aid Colombia received from the United States was only to be used for things directly related to the drug war.

The expanded 2003 Foreign Aid Bill asks that $731 million be given to Colombia and the Andean region. Of that amount, $400 million will go to the Colombian military and police.

Colombia is in the midst of a civil war, and has been for the past 40 years. The current government is headed by President Alvaro Uribe, who is the latest in a succession of unpopular leaders. The government is also involved directly with paramilitary groups who create areas like the “rehabilitation zones” the first speaker, Carolina Aldana, talked about. Aldana described the zones as places “where the military takes precedence over the elected government.”

“From a distance you may read that the war in Colombia is a war all about drugs, but this is not true,” Aldana said. “It’s a war about power, it’s a war about poverty, it’s a war about democracy.”

She described the current president’s ideas of security which entail, “controlling any manifestations of dissent, establishing military zones of military law, and doing whatever is necessary to militarily counter any insurgence.” This type of security, Aldana explained, does not address human rights violations or protect the population from anything other than perceived insurgency.

“As long as we have breath,” Aldana said, “we’re going to continue demanding and asserting that what we need is a different kind of state, a different kind of government that represents a participatory kind of society and that is going to break the vicious circle of violence and criminality that does not lead to any solution.”

In tears, Aldana concluded, “We don’t want you to be watching a video in a few years saying that the people that are on the panel today have disappeared,” referring to a short video showing activists who have disappeared, which was shown at the start of the forum.

Eder Jair Sanchez is from the department, or state, of Putumayo. Sanchez discussed the efforts of farmers and peasants in Putumayo who have been trying to develop reasonable alternatives to practices like crop fumigation.

Fumigation is one way that the United States destroys drug crops, but because the method, which is similar to crop dusting, is highly inaccurate due to the altitude from which herbicide is dropped, more than just drug crops are affected. In one case in Putumayo, a drift of chemicals reached a 5 km radius, and affected an elementary school.

In a letter to Christine T. Whitman of the US Environmental Protection Agency, several indigenous groups found evidence “that the spraying has caused significant health and environmental impacts,” such as eye, respiratory, skin, and gastrointestinal ailments, and the destruction of thousands of acres of food crops.

According to Sanchez, the peasant movement offered to manually destroy drug crops to avoid fumigation, but the government refused. The US State Department and the Anti-Narcotics Police in Colombia report that 30,000 hectares were sprayed between December 2000 and January 2001. “But when the follow-up was made to investigate the spraying of those 30,000 hectares, it turned out that 50% of the area that was sprayed was not planted in coca, it was planted in other crops,” Sanchez said.

“The most troublesome part, and the part that we brought to the attention of the international community, was the effect of the spraying on children,” Sanchez continued, “The effect is that it created some skin rashes, gave children continual vomiting, and headaches.”

In the past two years, 31 agreements have been reached between the peasant movement and the government, regarding fumigation and other policies. But little has changed because the government has not followed through with their promises of increased funds for infrastructure and social investment, Sanchez said.

This year alone, 5,000 families have left their homes in Putumayo and there have been 350 homicides, with 80% of the victims peasants. Several suffer health problems, particularly close to the fumigation areas. With so many problems in their department, the people of Putumayo asked President Uribe to come and discuss solutions. “But, he would only come if we did not discuss fumigation, and we did not discuss human rights,” Sanchez said. He concluded by reiterating how important it is for the international community to remain aware of the situation in Colombia.

With a voice slightly tired by yelling in support of striking SEIU janitors in Boston, Hector Giraldo came to the microphone. Giraldo is a trade unionist who has worked with the Federation of Public Employees in Colombia since 1980.

“I come from a very, very rich country,” Giraldo said, “rich in minerals, rich in petroleum, flowers, coffee, and many other resources. But, I also come from a country full of poor people, where children sell candy on the buses, on the streets, everywhere you look. Where the bridges have so many displaced people living under them, that there’s no more room for any more.”

Only seven percent of Colombian workers are organized into unions, and Giraldo explained that it is not easy being in the union. “Simply because we oppose the neo-liberal model, we have become targets of the paramilitaries. Because we oppose the privatization of health and education and other public services, because we denounce the corruption of the state.”

Between the founding of Giraldo’s union in 1986 and last year, 3,800 of their members have been murdered. Last year, 190 members were murdered. So far, in 2002 117 have been murdered. Teachers represent 34% of those killed, miners and energy workers represent 16%, health workers 13.4%, justice workers 4%, and other industries 6%. Although surviving workers provide police with the identification of those involved in the killings, nothing is ever done about them.

“We no longer have anyplace to hide in Colombia, that’s why we’re here in the U.S.” Giraldo and 27 other trade unionists are in the U.S. seeking solidarity from North Americans and educating them about where their tax dollars are going.

In the question and answer period that followed the forum, one Colombian student said that she has learned more about her country since coming to the United States than she learned while she was still there.

This forum was sponsored by the Applied Linguistics Department, the Hispanic Studies Department, the College of Public and Community Service, the Latino Studies Program and the Human Rights Working Group. The event was presented in Spanish and speeches were then translated into English.