Rotting Infrastructure Takes Priority As Retrofit Splits

December 10, 2004

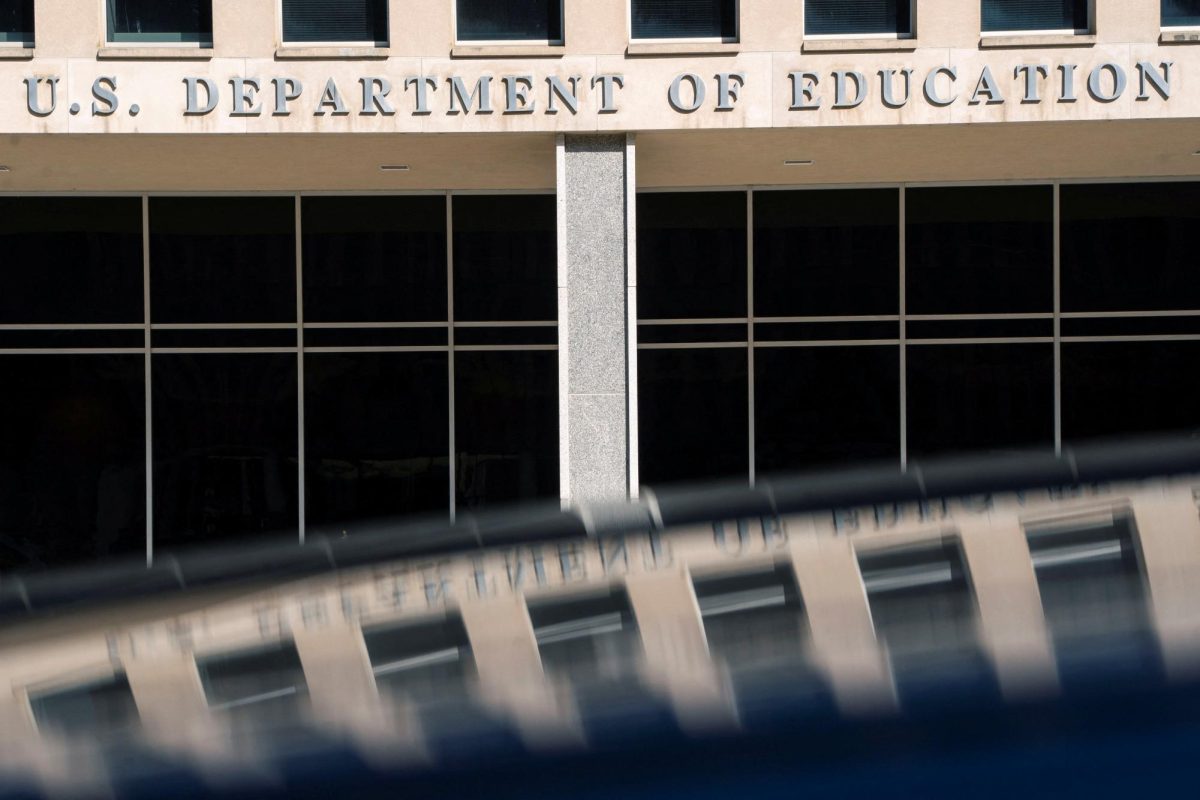

Retrofit, the renovation of spaces left over by the move of many university offices to the new Campus Center, is expected to be scaled back as UMass Boston administration officials seek to focus attention and funds on the upper and lower levels of the garage.

“The thing that’s really putting a question mark around how you’re going to do the rest of the retrofit is the deteriorating status of the upper level and lower level infrastructure,” said Ellen O’Connor, vice chancellor of administration and finance, in an interview with the Mass Media last week.

O’Connor called it “highly likely” that, in the next three to four years, the university’s limited capital dollars are going to be diverted to repairing the upper and lower level infrastructure.

“Certainly, the intervening urgency of the upper level and lower level is causing us to rethink what we’re going to be able to do to fit out the vacant space,” she said. “I guess the other way of saying it is if we didn’t have to worry about the upper level and the lower level, we’d put more money into the vacant space.” The deterioration of the upper and lower levels is mostly attributed to the poor design and construction of the “mega-structure,” which opened in 1974, and the salt water environment that surrounds the campus. The mega-structure, made up of two levels of parking spaces, is one foundation, on which the five buildings-McCormack Hall, Wheatley Hall, Healey Library, Science Center, and the Quinn Administration Building-sit atop.

Officials have been careful to stop calling it a problem with the parking garage, making a concerted effort to now describe it as the “mega-structure” and infrastructure that it is.

“We’re not calling it a parking problem, because people then think it’s, ‘Oh, you know, what’s wrong with those people over at UMass, why don’t they just park out in-‘ No, that’s not what we’re talking about. We’re talking about the infrastructure,” said O’Connor.

Structural engineering consultants, hired by the university, were opposed to answering definitively when the question of closing the buildings was put to them, instead giving administration officials an estimate of 10 years. “The rate of deterioration, if unaddressed, is going towards a time when the buildings will have to be demolished because construction will fail,” O’Connor said. “So I think we feel this has to be addressed, done, complete, fixed, within 10 years.” O’Connor, who arrived here from Brown University earlier this year, stressed the structure is still safe, and that a strong monitoring system is in place to keep it that way. “It is safe today,” she said. “It is that we are advised that, if nothing is done, then it won’t be safe tomorrow.”

Attempts to fund the infrastructure repair, which is expected to cost around $50 million dollars, are already underway. While having the state Legislature pick up the tab is “highly desirous,” university officials are not expecting it in light of the recent declines in the Legislature’s funding of public higher education over the last three years. At the recommendation of the UMass President’s Office, UMB officials say they are trying to set up a sort of matching program, in which UMass puts up some money and the Legislature follows. The program is said to be still in negotiation.

David Perini, head of the state’s Division of Capital Asset Management (DCAM), has already assigned an architect and a structural engineer to work with UMass Boston on the beginnings of the capital process to address the problems, O’Connor said, adding that Perini, who toured the infrastructure earlier this semester with UMass President Jack Wilson, is committed to helping UMB solving the infrastructure problem, which has been identified as one of the most important projects in the state. “It has been a growing problem, and it is growing faster than we have provided solutions for,” O’Connor said. The infrastructure is not only dilemma, O’Connor added. There are health and safety systems, information technology and other kinds of equipment, and other deferred maintenance that needs to be taken care of, she said, amounting to the whole package costing $260 million dollars. Studies are also underway for a new garage, with potential sites lined up. The cost of the new garage, $40 million, is already funded through the UMass Building Authority, headed up by David MacKenzie, UMass Boston’s former vice chancellor of administration and finance. UMB must eventually pay the amount back, making other projects more difficult and setting off another parking fee increase.

In comparison, UMass Amherst, the flagship campus, recently unveiled a five-year capital improvement plan, which, according to the Springfield Republican, will total $547 million. New construction will take up $193 million of that, with $173 million going to deferred maintenance, $5 million to information technology, $13 million towards code compliance, and $163 million towards renovations. UMass Boston has battled with the infrastructure problem since 1989, when it was first recognized. It was then thought by the university officials of the time that columns and beams would be enough to fix it.

In 1997, UMB, with current UMass Dartmouth chancellor Jean MacCormack at the helm of administration and finance, hired a consultant to do a structural review, which didn’t seem to get people’s attention. In 1998, she financed a facilities status report, which finally got DCAM to move in 1999. DCAM, which O’Connor said is constantly flooded with capital needs requests from across the state, performed an infrastructure review, estimating that $32 million would be required to keep garage/infrastructure operational. UMB, advised that it could be undertaken in six years, put together a six-year plan. In phase one, the university made a $1.4 million investment, which included recovering the roofs and re-doing the façade of the Healey Library.

Consultants then came in and said it wasn’t going to cost the original amount for phase two, $2.6 million, but nearly $10 million. This led UMB to ask Walker Parking consultants to do a total review, which ended up saying the cost will be $42 million, with another $8 million to replace electrical, plumbing, mechanical systems in the pipes that run through infrastructure.

When university system officials saw the April 2003 report showing the deterioration of the infrastructure within 10 years, they demanded to know what the campus knew and when did it know it.

O’Connor said reports received by past vice chancellors were, at the time, accurate reports. But the next time someone would come in to take a look at it, the situation had gotten worse, she said. “They were trying to solve the same problem,” she said. “[But] the solutions were not powerful enough.”