POPaganda

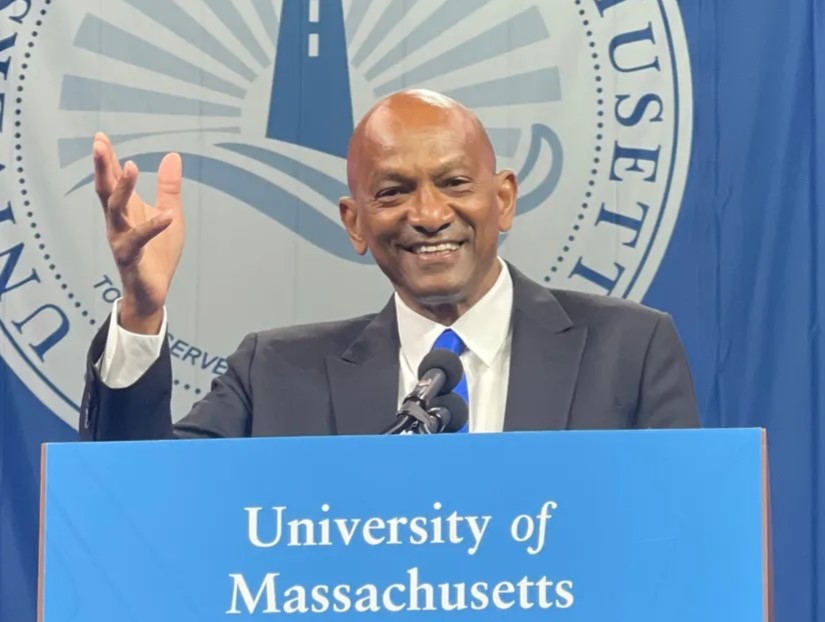

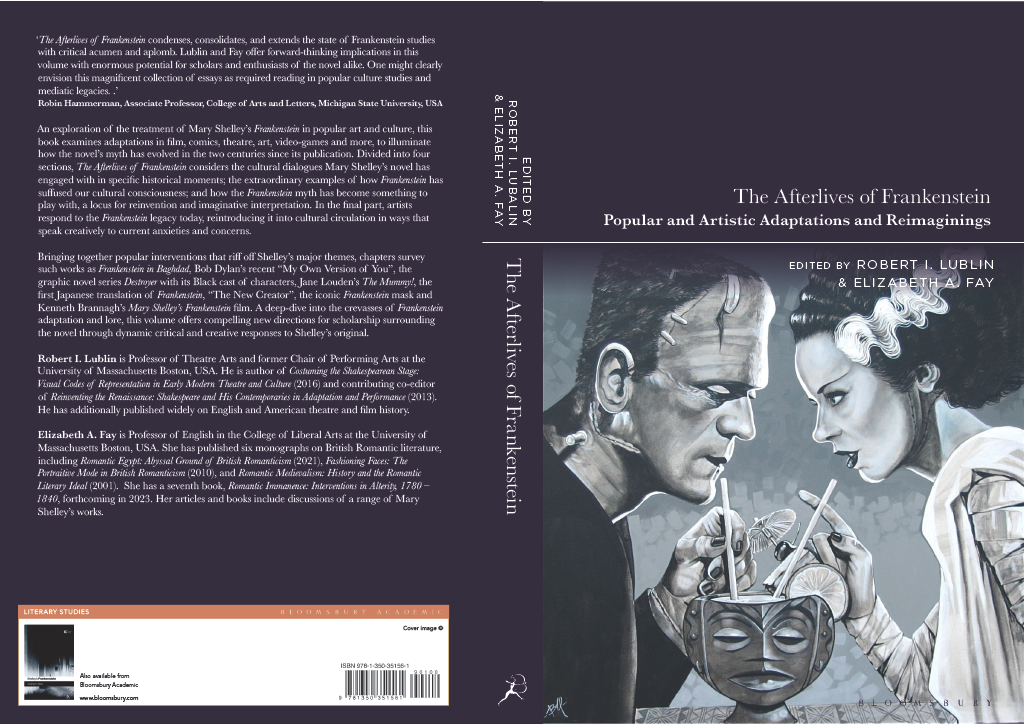

The Unbearable Likeness of Being, 2003

February 10, 2005

Ron English: total art rebel or just total ass? Now you can make that decision for yourself by catching a viewing of the new documentary about the notorious artist and his even more so work, POPaganda: The Art and Crimes of Ron English currently showing at the Museum of Fine Arts from now until February 12.

Ron English’s artwork over the years has been hard to ignore. Part of this is due to the fact that many of his most famous works never made their way on to the finer museum walls, but instead were plastered thirty feet in the air on the sides of mainly New York and New Jersey’s highways and byways.

Ron English seems to suffer from an acute case of self-described obsession with putting his art up over billboards and other preoccupied advertising spaces (as hilariously explained in a clip of Ron and his wife’s deadpan delivery of how his obsession with art was ruining their marital relationship on some obviously clueless conservative talk show).

Although he began using the billboard-as-medium technique simply as a way to simply liberate his art, through the inherently illegal act of covering existing billboards he was able to get his art to the people and subvert the established art house crowd, but soon the medium affected his message. English began using the very concepts of advertising, the images, the logos, the slogans, in his work as a means to undermine the messages normally connected with these concepts. At this point in English’s career, much of his art had clear political aims. One of the immediate targets that he took shots at were cigarette advertisements. So, Ron English made up a series of Cancer Kids pieces featuring the popular Joe Camel from Camel Cigarettes as a baby and, of course, still smoking those delightful little cigarettes. In the film, Ron talks about how he felt that the Joe Camel character was a direct attempt made by the cigarette companies to advertise their product to minors.

What he’s doing, however, goes beyond simple satire. He is acutely aware that advertisers use a specific image or logo because it identifies the company and also carries with it loaded messages, usually something along the lines of coolness, hip-ness, or youthfulness. By using the very same images of the mass media (not us, of course) and reappropriating them, they now take on a new meaning. After seeing one of his posters featuring an obese Ronald McDonald next to the words MC Super Sized, it’s hard to look at the clown-faced hamburger peddler the same way again. Even beyond the anti-corporate message that’s on the surface of Ron English’s art, his work tackles issues of free speech and public and private property. Some people (mostly the owners of the corporations that sue him) feel that English has no right to vandalize private property. Obviously he has no legal right, as his countless arrests have shown, but it raises the question of who owns the public visual field.

English explains in one point of the film how his work is a logical extension of his environment. How classic painters who lived in the mountains tended to paint mountains; English lives in the city, where product advertisement has found it’s way into most every available space that can be seen or heard. English is simply responding to that. The combination of the sarcastic wit of such simple slogans such as “Jesus Drove an SUV/ Mohammad Pumped his Gas” or “Support our CEOs,” along with English’s and other’s discussions on the philosophy behind their illegal street art is what really warrants this documentary being made.

English responds to the argument that since he’s an established artist, he is sufficiently capable at this point to simply rent out the billboards and not have to deface private property, by noting that because of the often controversial nature of his work, he would never get the proper clearance to allow him to continue to say what ever happens to be on his mind. He also describes how he has learned to do his work during the daylight because at night it’s too obvious that he’s up to illegal activity. The part of the documentary, which was directed by Pedro Carvajal, where it begins to wane is when the film shifts over to Ron English’s studio work. This is not to say that this work, which is an extension of his refiguring of pop-culture icons, is not without any merit. It’s just that, as a documentary, it’s far more compelling to follow the phenomenon of billboard liberation rather than just a biopic on just another eccentric artist. But still, Slash from Guns and Roses makes an appearance.

POPaganda: The Art and Crimes of Ron English will be running at the MFA until Feb 12. Check out www.mfa.org or www.popaganda.com for more info.

The Collector, 2003-04