Minority the New Majority

OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

October 23, 2003

Half of them were from outside the United States. Nearly all spoke two or more languages. They were from Roxbury, Dorchester, Boston, Somerville. They were Native Americans, Asian Americans, African Americans, community activists all. And they all converged early one Saturday morning at UMass Boston to speak up and set an agenda.

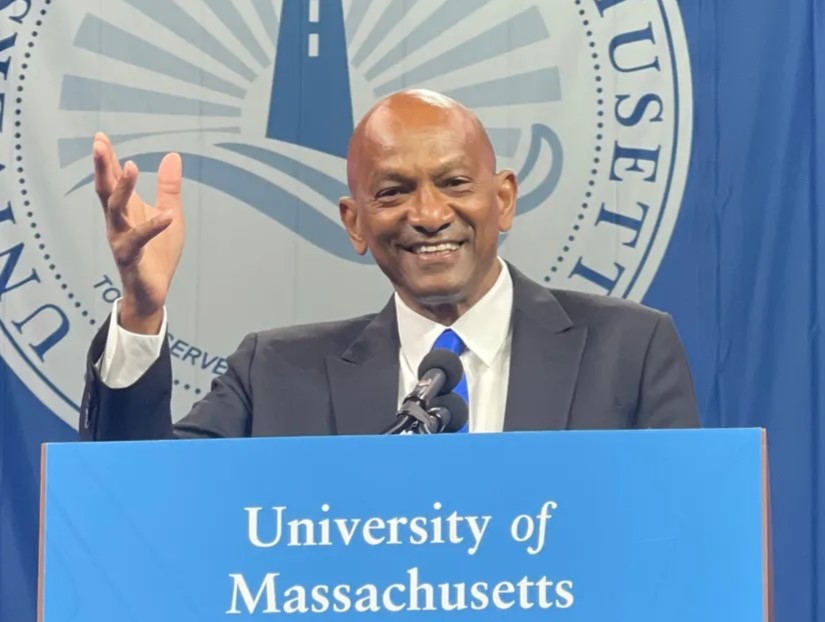

Known Boston activist and keynote speaker Melvin King, celebrating his birthday, took to the podium in the Lipke Auditorium. “This coming together is something I have dreamed about, hoped for, wished for, strived for. And to be honored with the opportunity to speak is very, very moving,” he said, comparing it to the time he introduced Nelson Mandela when the South African leader came to Boston many years ago.

The day’s goal was for minorities, who now make up much of the city, to “move from isolation to inclusion, to move this city and change its dynamics.”

King called for the group gathered there to increase the level of coordination between leaders, organizations, and communities.

The hundreds of people then split into different groups to strategize and discuss various topics: civic and political participation, civil rights and immigration policies, education, economic development and workers’ rights, and health and human services.

It’s a “historic occasion,” said Boston City Councilor Chuck Turner (District 7), who was in the audience and is an ex-officio member of the New Majority. “We owe a debt of gratitude to UMass and particularly the Trotter, Gaston, and Asian American Institutes for their invaluable support for people of color in Boston to come together.”

Paul Watanabe, an associate UMB professor and co-director of the Asian American Institute, called it a “great day.”

“The fact that we’re drawing from experiences, expertise, and wisdom from one of Boston’s resources, the people who exist in its communities” is terrific, he said, acting as the recorder for one of the groups, Civic and Political Participation. “I look forward to building something here.”

Lydia Lowe, executive director of the Chinese Progressive Association, was a moderator of one of the Civic and Political Participation discussion groups.

She told of her experiences fighting the development of luxury apartments, and calling Boston Mayor Thomas Menino every week for a year and a half, never getting her phone calls returned.

She also spoke of the past primary, held last month, and made accusations of electoral fraud. Poll workers were telling the elderly who to vote for, she said. It’s hard for Chinese people to read the names, since they don’t know the alphabet, she explained, so they vote by numbers, by how far the person was down on the ballot.

People would come in wanting to vote for “Number 11,” or Felix Arroyo, Boston city councilor-at-large. The poll workers would come over and ask, “What about Numbers 6 and 10?” (current councilor Michael Flaherty and candidate Patricia White), she said. Some would even mark off the ballot for the people.

Arroyo, who is seeking a ban on Boston University’s new bioterror laboratory, and once fasted in protest of the war on Iraq, is the city’s first Latino councilor, and came in fifth in the primary with 14,379 votes. White took third place with 16,439 votes, while Flaherty had 20,307.

“People like to talk about voter apathy,” said Lowe. “If people take the time to come out and time and time again they’re ignored, they’re going to lose faith.”

UMass Boston was also there through the volunteers. Riche Zamor and Fritz Hyppolite of the Black Student Center, and Kristina Lopez of Casa Latina were among those spotted there.

“It’s a great event that speaks to a great number of issues with in the communities of Boston,” said Hyppolite, also a student senator. “And it shows the significant role UMass Boston can play as a public institution that reflects the diversity of these communities.”