Emphasis Put On Research With New Hire

October 14, 2004

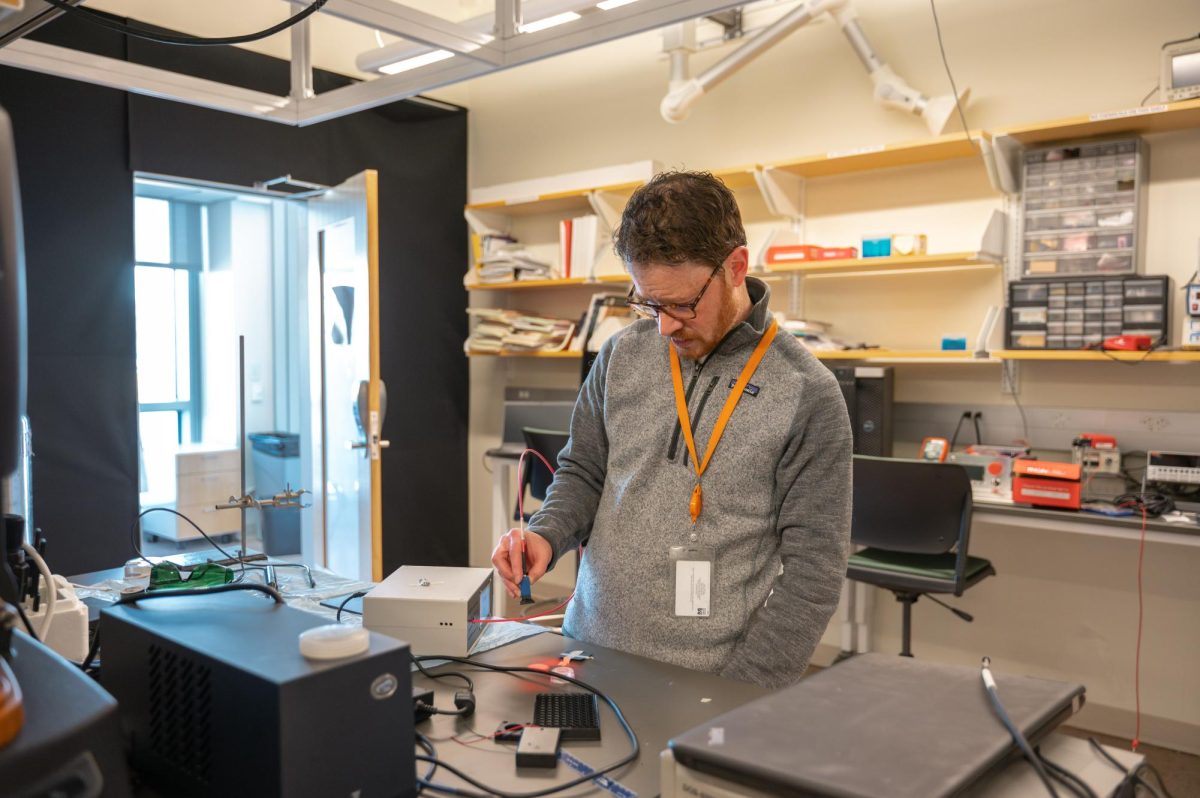

Seeking to put greater emphasis on research and the dollars it brings in, the university has created and filled the position of vice provost of research in order to support its pursuit of $50 million by 2008.

“You need somebody who gets up in the morning and focuses on that,” said Paul Fonteyn, provost and vice chancellor of Academic Affairs.

“We now have the status of a research university, but we have not really shaped the infrastructure that corresponds with that status,” Associate Provost Winston Langley said. “The hiring of a vice provost is a major step in seeing to it that the research infrastructure is developed in a manner that is consonant with the research status to which we aspire.”

A vice provost of research’s primary job is to help faculty develop a system for seeking out grant opportunities, writing grant proposals, getting pre-award grants, and managing the grants when they finally come in. “In other words, the person at the university who is responsible for the research enterprise,” said Richard Antonak, nine weeks into his new job, having been hired away from Indiana State University.

Antonak insists that his job is more than just pursuing big government grants. “I don’t want to limit my work, my effort only to chasing federal money,” he said. “That’s typically what people think about a position like this, is increasing the number of federal dollars. It’s much more than that.”

Antonak says he is hopeful that he can help assist faculty, graduate and undergraduate students, and staff to obtain resources needed to successfully work on their research.

It could be helping a music professor get private funding to publish a composition or a microbiology graduate student get the resources to do research in Alaska next summer, he said, or an English or history professor needing to go to England to see a Chaucer manuscript. “I don’t define what the substance is,” he said. “My role is to try to help people find the resources they need to be successful.”

When he left Indiana State, it was just shy of hitting the $20 million mark, built up from a little under $10 million when he first arrived there five years prior as chief research officer. “I take no credit for that,” he said. “The increase was because faculty, and students, and staff went to the trouble to write a competitive proposal.”

The only credit he could take, he said, was supporting and encouraging the groups to go after the funding.

The goal at UMass is higher, with the university shooting for $50 million by 2008. “I have no doubt we will do that,” Antonak said. The university is currently at $34 million. While looking at other job opportunities at various locations, Antonak says he already knew about UMass’ reputation as an urban institution committed to access and excellence. “It was very clear to me that this institution was pretty close to a perfect fit for me personally and professionally,” he said. “I am absolutely convinced it was the wisest decision I’ve made in my life.”

Other factors came into play in his choice, he said. “It was located in an urban center. It had a clear vision for its future, as spelled out in the university strategic plan,” he said, noting that one of ex-Chancellor Jo Ann Gora’s three R’s was research. “What that told me was that this university was committed to increasing research activity and success of faculty as well as staff and students in research.”

For the two months he’s been here, Antonak has been attending seminars, faculty and department meetings, and gone to check out the campus’ labs.

“The sense I get about this institution is that people feel good about UMass Boston, about being part of UMass Boston, they feel good about future,” he said. “That makes my job so much easier.”

But with a heavy course load, faculty may not be getting in as much research as they’d like. “It is true that the teaching load of the faculty is generally too heavy for the type of research we are expected to engage in, and the provost is committed to seeking an alignment with research and teaching that will reflect a greater balance,” Langley said. “How this is going to be developed will involve the university community as a whole.”

It was the faculty, administration officials say, that were pushing hard for the job, wanting to do research and look at grant opportunities. “It really wasn’t something that was driven from the top,” Provost Paul Fonteyn said. “It was something the top was responding to.”

When Fonteyn was being interviewed for the position of provost, at the same time a search was on for a position similar to vice provost of research. But the university was unsatisfied with the pool of applicants for the job. Fonteyn, once it became clear he had the job of provost, managed to convince Gora to hold off on picking a vice provost until he could set up his own search. He wasn’t sure the pool of candidates he had fit the bill, and he also wanted to be able to interview them, he said, since the person would be working closely with him.

The position is a new one for UMass Boston, and Antonak is the first to occupy the office, much like Fonteyn was the first vice provost at West Texas Tech and San Francisco State University. “Like Richard, I was the first guy on the block,” he said.

“What the campus can expect and what they have seen in the past couple of months is a fellow with a beard going around listening,” said Antonak. “Once I feel fairly comfortable what I know not only what people want to do but what they need in order to do it, the campus will start seeing the rollout of some initiatives.”

Both Fonteyn and Antonak were down in Washington D.C. all day last week meeting with the National Science Foundation (NSF) talking about different types of programs. They were joined by Dean of the College of Liberal Arts Donna Kuizenga to talk to the National Endowment for the Humanities on grant possibilities and the U.S. Department of Education for the improvement of post-secondary education.

“So that’s how you do it,” Fonteyn said of talking to proposal officers about what they look for in a particular proposal. “You find out what new things may be on the horizon.”

Senior administration officials point to the Environmental, Coastal, and Ocean Science (ECOS) Department, the Biology Department, the Center for Community Inclusion in the Graduate College of Education, and the Psychology Department as some of the research hotspots on campus, with various areas working on health disparities, public policy, disabilities studies, and homelessness.

Fonteyn declined to speculate on where the “hotspots” are, saying the term demeans other grants that are in competition. “I don’t like ‘hotspots,'” he said. “I don’t think it’s fruitful to address it that way.”

Fonteyn called faculty key to the research, noting that several have received Research Opportunity 1 (RO1) grants, which he labels the “most difficult” and “prestigious” to get.

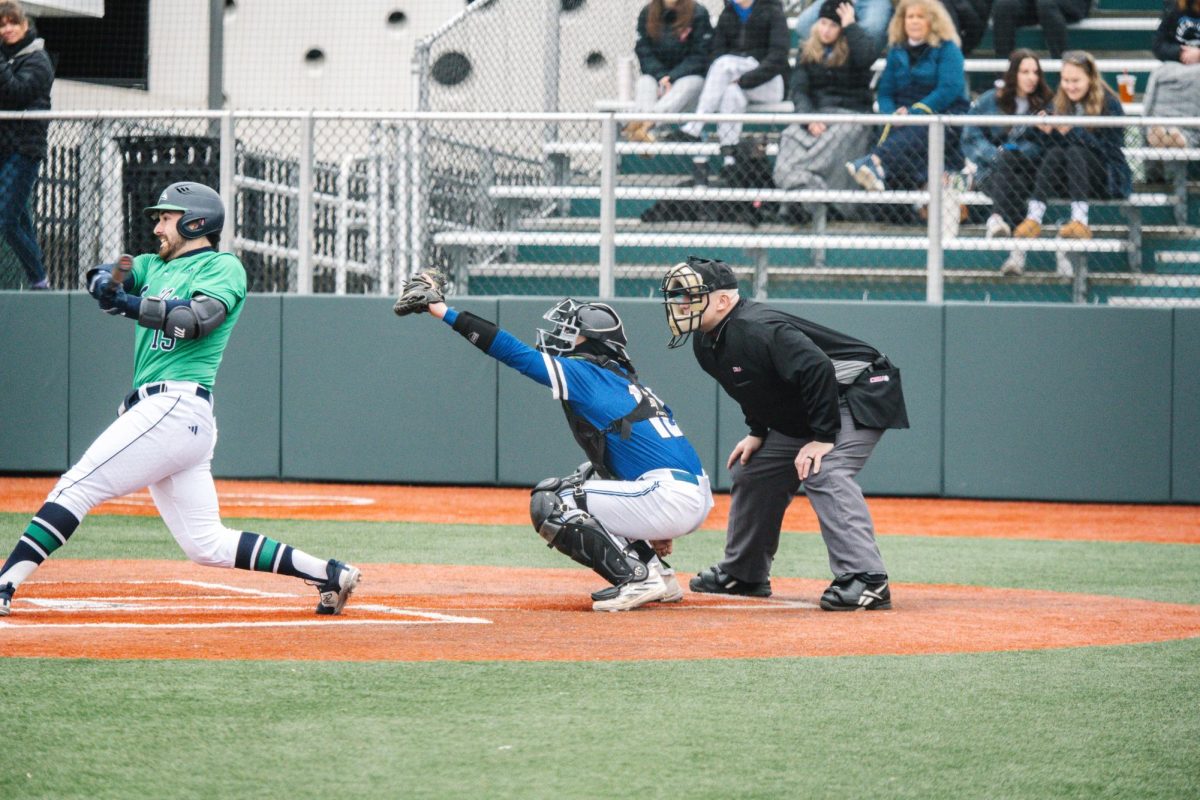

“You could hire the best coach in the world, and you may play the best team in the world, but if you don’t have the players, you’re not going to win,” Fonteyn said. “You may win, but you’re not going to win at that level. What I find here is that we have actually a much easier task, because this place has a tremendous amount of talent.”

That was proven, Fonteyn said, by the $12.5 million dollar NSF grant that was recently presented by U.S. Senator Edward M. Kennedy for a science education reform program in Boston’s public schools. Fonteyn said there were 135 proposals total for the grant, with UMass Boston professors out-competing the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Boston University for it.

“All they needed were some support structures,” said Fonteyn.