Hot Media & Oscillating Sound

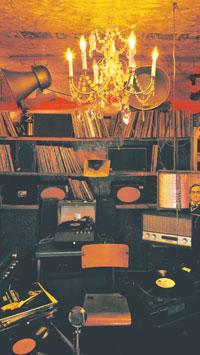

Opera for a Small Room, 2005 b Sissel Tolaas Synthesized human sweat pheromones micro-encapsulated and embedded in white paint on gallery walls. Photo by Elizabeth Beer.

October 23, 2006

Media critic Marshall McLuhan once described a night out at the movies as a being an experience of “hot media,” as opposed to staying home and reading a comic book – what would have called a “cold media.” What McLuhan means is that film takes advantage of several of the viewer’s senses at one time, and you, the viewer, are able to achieve a greater level of participation through sensory interaction during the experience. A comic books engages only a single sense.

For better or worse, much of the fine arts fall into the category of this “cold media” – a painting on a wall or a statue in a corner. You may not agree with McLuhan, but this approach does suggest an interesting critique on how the fine arts rarely create little in the way of a multi-sensory experience beyond what already is offered in the real world, such as a film, or heck, even a comic book.

From now until December 31, The MIT List Visual Arts Gallery is showing Sensorium: Embodied Experience, Technology, and Contemporary Art , which aims at being more than just your typical two-dimensional, single-sensory, sit-back-and-let-the-art-do-its-thang gallery experience. The five artists involved combine art expatiations with both elements of technology and the human senses. No single piece manages to involve all five senses, but together they create an experience that challenges the viewer in ways that subvert the roll of just casual observer. Sensorium invites you to step inside each piece and engage in it, not just with visual passiveness, but to take advantage of its rich sensory environments.

Walking into Mathieu Briand’s Ubiq: A Mental Odyssey you are able to pick up on its cinematic analogy even before you may have had a chance to read the title of Briand’s piece. As you enter the small white room, the streamline inorganic forms and antiseptic surfaces create the aesthetic of Kubrick’s futuristic vision of the year 2001. Like a space age command center as seen through the lenses of a 60’s futurist, a red-cushioned bubble chair faces outward against a large display screen which shows a twirling satellite feed of Earth. Unmarked, unlabeled, and probably nonfunctional buttons and displays emphasizes that the viewer is a bit out of place and out of time in this dated vision of the future.

Four columns make the rooms exit as well as being inset with shelves that hold helmets attached by spiral-bound stretch cords to a single-button controller. You are invited to put the helmeted contraption on along with other viewers who are freely allowed to wander and explore the room. Small video display screens attached to the helmets rest directly in front of your eyes, as a top mounted mini-camera records your immediate field of vision. Clicking the button on the hand held controller toggles the display screen, shifting between your own visual field and that of other viewers.

The next room doesn’t immediately make it clear that it is a separate piece. By placing Sissel Tolass’s Fear I next to Briand’s, draws a parallel between the two pieces. Though Hagighian’s continues the idea of visual minimalism in its towering white walls, it does not share the same self-consious approach to its ascetic. Nothing divides the room except for single black numbers that suggest the walls are divided into segments – faint finger smudged, and lipstick marks dot the surface at just about finger and lip level.

Like giant scratch and sniff stickers, Fear I’s walls invite the viewer to experience the piece’s tactile and olfactory nature. Little in the way of visual presentation, Tolass’s piece presents itself as a purely tactile and olfactory experience. The audience must rub the surface of the walls, surfaces which have been rubbed, scratched, touched, fondled, and bumped into by countless others. Not all of the scents produced are immediately recognizable or even comparable to those that are encounter in everyday experience. Licorice, grass, and variation on the two were the most easily identifiable, but someone also mentioned a bit or coriander as well. More than easily recognizable scents, the piece allows the viewer to bring their own experiences to make associations with the smells offered by Tolass. Often the smell manages only to illicit a color comparison – one panel might smell “blue,” another “green”. In a room limited only to the most basic of color pallets, this effect can be striking.

Ryoji Ikeda’s Spectra II and Cardiff and Miller’s Opera for a Small Room both achieve their level of sensory manipulation by immersing the viewer with in the works themselves. Spectra II consists of a long hallway obscured by complete darkness except for a thin red laser line that rests against the far wall or the occasional burst of strobe. The extreme light deprivation paired with extreme aural manipulation create audio and visual distortions that can overwhelm the viewers senses – like an epileptic nightmare. A sign outside Ikeda’s piece warns of its intensity and reassures the presence of an exit door at the end of the hallway.

Opera for a Small Room echoes this idea by enclosing the viewer within an isolated space and then proceeds to assault them with a collage of light and sound. A small shack sits in the center of the darkened space filled with light bulbs, tin cans, and thousands of records spanning pre-war Americana. Several turntables are programed to switch between albums and recorded sounds of trains, animals noises, vocal narration, and original scores. The lights within the shanty cabin pulsate along with the intensity of the sound.

Ultimately the MIT List Visual Arts Center’s exhibit Sensorium does manage to fuse the often desperate elements of art, technology, and the human senses into this multi-artist exhibit. In a world where fine art is not always at the vanguard of life’s experiences, but instead reflecting it, ts refreshing to see artists like Mathieu Briand, Sissel Tolaas, Ryoji Ikeda, Bruce Nauman, Janet Cardiff, and George Bures Miller break from cleche and push the art world beyond its normal confines.

But were they successful in their attempt? Lets just say, they were close enough that I could almost taste it. Almost.