Dateline: Kenmore

Dateline: Downtown

September 4, 2007

Death is a grim topic, no fun to talk or read about. In some cases, though, when there is not a beautiful young life halted by nonsense or a dignified old one done in by a disgrace, but when it is timely (such as it ever can be) and on one’s own terms, it is hard not to mingle grief with admiration at the bang someone went out with.

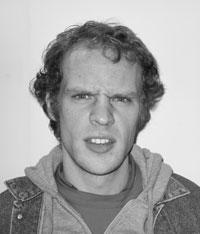

He roamed, rapped, guzzled, harmonica’d, howled, and sweat in Kenmore Square for twenty years until Boston University kicked him out and carpeted the place over, whence he retired to Allston-Brighton, where he died in a dramatic scooter accident last summer. He would have been pleased to know the details, I’m guessing; the accident was loud, explosive. The papers said he was going fifty miles an hour on the scooter, which he had bought, according to local business owners, with money he had saved. He told our friend Ross, two weeks before the crash, that the thing was going to kill him, and it did. No casualties but him and the pole. That’s good. Mr. Butch was a kind guy.

Butch also liked noise.

Spashhh!

“STOP SMASHING BOTTLES!” he screamed in back of the Rathskellar, smashing an empty Olde English “800” with his left hand and a Schlitz with his right when I met him. He was flamboyant and loud, but he also operated with a conscience and liked peace. He broke up or averted many fistfights in his role as scene cop, when not drinking one of a thousand clear glass or plastic pint bottles of Rubinoff or Rebelska or some other S.S. Pierce family vodka that would poison Pushkin in the sunlight on Commonwealth Avenue or in the murk of the Rat alley. He swept sidewalks or floors (with Godfatherly confidence that the favor would be repaid), helped the elderly and disabled across the street (done gratis), amused college students and Sox fans in exchange for their MON-EEEE, which he enjoyed assuming, and told a confused, angry young kid whose head was blowing up that he had a good heart and so he’s got to do something good for other people while he can. ‘Cause you only got one chance.

An obscene tangent of his came to my mind a second ago. It’s killing me, but I can’t share many anecdotes of him with you, because I like my job on this paper good enough. Ask me in person. Here’s one that belongs to a friend, who ran away for a few days when she was sixteen. Her Mom discovered, through her daughter’s friend’s father, that there would be a show that night in Kenmore Square, at this place called the “Rat Killer”, that the girl would be at. The Stepdad wanted to investigate. “Who are her friends?” he asked, wanting names, faces. The friend’s mother could only provide her own daughter and a “Mr. Butch” the two friends were talking about, who sounded like some character. Stepdad rushed over, his head no doubt full of suspicions and dread.

The girl, though, over the course of the night had had a fight with another friend of hers. So, she was feeling blue and decided to go home. The mother woke up to discover her daughter home, but not her husband. Where was her huband?

Oh, he showed up home at two in the afternoon. He and Butch had spent a wild night. “It’s OK, honey,” he said. “We stayed at the HoJo’s.” The story, as best as we could piece it together, is that the Stepdad found Butch (which wasn’t hard) and commenced screaming at him. Butch must have placated him; the two men ended up drinking together at length. As day turned to night and night crawled the stepfather decided “Ah, hell,” to shack up at the Howard Johnson’s just out of Kenmore, and treated his new drinking buddy. Both men slept in the room, a fact mined for its implications by my friend. “My Dad slept with Mr. Butch,” she brags, though Stepdad swears he slept on the floor.

In the wake of his death everyone who knew him had stories, like he had stories, which he spun nicely; Butch could tell a cliffhanger with an actor’s expressiveness and a good sense of timing.

He is said to have been a fiery performer as a musician, but I never saw him onstage, just on the street. But past the spectacle of the Mr. Butch Show you could sense a dignity that was unmovable, formidable, impervious to the street. There was something quiet in him that was very impressive, subtle, that you missed if you only paid him attention when he was going off. You’d catch moments where some internal mechanism would lead him to instinctively do what is known as “the right thing”. He protected the weak from the strong, the dorks from the skinheads. I watched him do it over and over again.

Mr. Butch was a freak, seeking freedom. No boss, no landlord, no ball and chain. He did not work a conventional job for wages, and while certainly not adverse to a handout had a strong sense of reciprocity under his dreadlocks. Whenever there wasn’t someone hooking him up with something- a beer or a slice of pizza or a few bucks or some giggle smoke- he was helping someone out. Something for the bourgeois to envy and their kids to romanticize. He made Kenmore his home base in the mid-’70s, just planted himself like an Old Testament patriarch as the neighborhood swirled with life around him, with new students every year and with new punk rockers as the old ones died or got real jobs. Even his amigos, Indian Dave or Mike the Rock or Ronnie, came and went, but Butch was exclusive to his area. He didn’t need to move around to be where his kind of action was.

Every place worth living in has someone who excels description, whose character and qualities are impossible to relay precisely because they belonged in a time and place that is not now and here. If you saw Mr. Butch yodel and jump jacks and skateboard and outdrink everyone all day, every day and every night, with a napping kitten hidden in his coat, when Kenmore Square was still smudgy and turbulent, then one could begin to understand Mr. Butch, or Harold Madison, Jr. You’d think you understood him, maybe, but then a power you didn’t recognize would arise in him. He wasn’t just what you saw. All you could do was accept him on his terms, grateful for who and what he was. Lots of people will miss the hell out of Harold Madison, Jr.