“The Shape of Things” shapes up nicely

March 11, 2009

What is intimacy? What is art? What is love and how far are we willing to go to get it?

The answers to all of these questions lie at the heart of Neil Labute’s “The Shape of Things”, which was recently performed by the UMass Boston performing arts department as part of their spring production schedule.

Like most of LaBute’s work, the play is an intense look at relationships through a gritty lens of realism, in this case focusing on the lives of four characters at a small Michigan college. The driving force in the plot is the developing romance between Adam, an overweight smart-aleck loser who works as a security guard at the campus art gallery and Evelyn, a beautiful free spirit who Adam meets on the job when Evelyn threatens to deface a statue that he is guarding.

From there, an intense romance unfolds between these two opposites as Adam falls head over heels for the beautiful, exciting, and sexually alluring artist. Much to the surprise of his two close friends, girl next door Jenny and cocky Phil, on the verge of their own nuptials, Adam begins to change his ways. He loses weight, begins wearing contacts, upgrades his wardrobe and even goes so far as cosmetic surgery to improve himself, all at the gentle urging of Evelyn. But does she really care? And who are all of these changes for?

To complicate matters, there has always been chemistry between Adam and Jenny, and as Adam becomes more confident as a benefit of all of his superficial improvements, he becomes bolder in fanning the flames of his latent desire for Jenny. Meanwhile, Jenny and Phil, who is also Adam’s best friend, are having a bad case of the pre-wedding jitters leaving her open to the new and improved Adam’s advances. The play culminates in a twist that calls all of their actions in to question, but also opens up a discussion about some of the themes that run throughout the story and how these larger, abstract concepts affect the characters in very real ways.

This embracing of contemporary realism to a degree some might go as far as to call bitter at times while simultaneously being willing to tackle some of the larger ideas presented in the work are just some of the reasons that director Carrie Ann Quinn chose this production as her campus directorial debut.

“This is just a play that I’ve always wanted to direct, and I think that it is pushing the boundaries enough and is interesting enough that college students would really like it”, she informed. “I am a Neil Labute fan, and there’s a lot of controversy over whether he’s a misogynist in some of his other works, but mainly what I like about it is that he asks questions and incorporates intellectual discussion, such as art, and what is the nature of art, with normal love-relationship issues. You don’t usually get a lot of plays about college students that question a lot of larger, universal things and don’t just ask things like ‘should we date’, ‘are we gonna date’…break up stories. I also really love the dialogue, which is very quick, with a lot of interruptions and I think it is really fun for the actors to work with.”

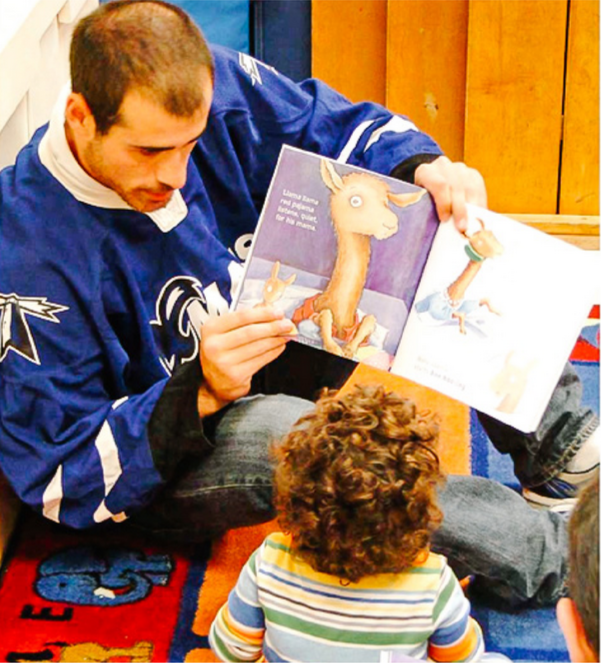

Because the story is so centered around the relationship between Adam and Evelyn, the production itself very much depends on the on-stage relationship of the actors playing the two leads. Sophmore Zach McCoubry (Adam) and senior Danielle Frongillo (Evelyn) have a palpable chemistry that brings tension and energy to every moment of the show, which is part of the reason why Quinn cast them as she did. As Evelyn, Frongillo owns the stage from the minute the lights go up and exudes an intensity that can be felt at the back of the theatre. Her portrayal of the vampish young artist is unique, because despite a glut of morally ambiguous behavior, she manages to remain likable throughout and plays the role with a confidence that seems unshakable from start to finish. She is always in control, and we know it. In stark contrast to the extroverted and brash Evelyn, McCoubry’s portrayal of the Pygmalion-like Adam shows an impressive range, as the character slowly transforms from understated, nervous and action-packed with neuroses to a cool customer who is willing to take risks and make choices. The metamorphosis is gradual, but noticeable, and McCoubry plays every stage with a distinct sense of balance between who the character is when the story begins and the final product that we see once the change is complete.

Another fascinating element of this production was the way that the stage was designed to be almost, as Quinn described it, a piece of art unto itself. The scenery featured a number or works of art by UMB students and was presented in an aesthetically pleasing way that was meant to connect with some of the artistic themes prevalent in the story. By subdividing the limited space into three smaller segments, Quinn made excellent use of what she had and eliminated the need for major changes in the set between acts while still giving each section a quality of its own that really worked to bring the audience into the world of the characters.

This show was actually made into a feature film in 2003 starring Paul Rudd and Rachel Weisz as the leads, and in that medium, the transformation at the core of the story was allowed to take place over a longer period of time, which made this reviewer incredulous as to whether a stage production of the play could be pulled off in only ten acts. It was pleasantly surprising to see how the cast of four was able to tease out the changes in each character without relying on makeup or movie magic to drive home the point. The changes were exemplified through small idiosyncrasies and subtle changes made by each performer that were woven together to create a complete tapestry.

Overall, the acting, production values and technical details were stellar, the only minor annoyance being the choice of music that was played during the scene changes, which seemed disjointed from the story and at times hindered the flow of the play. But when your musical choices are the biggest problem, and they are mainly exhibited when the lights aren’t even on, it means that you’re doing everything else pretty damn well.