Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things – Stay off the grass

Children Shouldn’t Play with Dead Things

May 4, 2005

BY DENEZ MCADOOStaff Writer

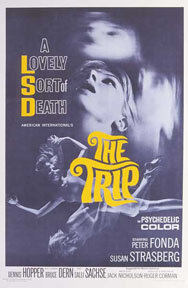

The Trip1967Director – Roger Corman”Listen to the sound of love. Feel purple. Taste green. Touch the scream that crawls up the wall!”85 min. – not rated

Stereotypes can be kind of fun sometimes. Let’s go ahead and see if we can name the decade-specific counter culture stereotypes in American history over the past half century. In the ’50s had greasers and beatniks; the ’60s had mods and hippies; the ’70s teemed with punks and disco divas; the ’80s gave us new-wavers and hair metal-maniacs; and the ’90s brought gangsta rappers and grunge rockers into the American mainstream. So what’s in store for the illustrious zeros? Metrosexuals and Paris Hilton wannabes? Yeah well, we’ve still got five years to try and redeem ourselves.

Boy, how do I love condensing cultural movements into easily identifiable and dated buzzwords and fashion clichés. The only people who seem to love to do this more than me is Hollywood, and no one was more the cultural punching bag than the hippies. Poor little misdirected idealists; you’re so cute with your love beads, those bell-bottom pants, and that pungent granola smell of yours.

1967’s cult classic The Trip is pure psychedelic-era exploitation. The token hippies are appropriately stoned, the straight world is characteristically stuffy, and the gratuitous use of the word “groovy” might just make you want to punch something nearby. Luckily, all of this only matters during the film’s first 10 minutes. During these 10 minutes you will either laugh or cringe, depending on your level of fondness for the decade that invented Jell-O, as cult film mainstay Peter Fonda struggles with the pressures of both his job as a TV commercial director and his estranged wife as they begin to finalize their divorce. Peter Fonda, who played the captain America character in the somewhat less-clichéd period piece Easy Rider, stars as Paul Groves who is just looking for some escape from his hectic life. He speaks to an Allen Ginsberg-type guru character, played by Bruce Dern (who was reportedly so anti-drug culture he had to ask director Roger Corman what LSD was before accepting the role), who suggests that Paul try this new drug that’s all the rage, known as LSD. Since this is 1967 there are still a few more years until Brian Wilson-type acid casualties really start to send the message home that a few hits of LSD won’t in fact turn the world “on” and bring us a land of peace, love, unity, and respect. That’s what Ecstasy is for.

Anyways, at this point the film becomes roughly an hour’s worth of acid trip, right to the last head-scratching minutes that the film’s production company, b-movie factory American International Pictures, forced director Roger Corman to tack on in an attempt to oppose the otherwise ambiguous message of the film. It doesn’t clearly appear to be either condemn or condone drug use, but instead seems to aim to reproduce a fairly accurate representation of the LSD experience. Even though the accuracy of the hippies is a bit ham-fisted (though the appearance of Dennis Hopper is always nice) and the “groovy” special affects are limited by a tight budget, The Trip manages to bring the viewer along an emotional roller-coaster ride where images are sometime brilliant and fascinating, and other times chaotic and paranoid. Watching this film can at times be an uncomfortable experience, especially when its difficult to separate the fantasy from the reality, but, this is exactly what makes The Trip so convincingly authentic. The screenplay was written by Jack Nicholson, based on his own experiences with LSD and the divorce with his first wife. Reportedly Fonda, Hopper, Nicholson, and Corman all took LSD in preparation for the film, with the experience being Corman’s first time. He enjoyed it so much he had to ask the others what a “bad trip” was so that he could ad it into the movie.

Ultimately The Trip works more as an exercise crafting surreal visual landscapes that posses an emotional ebb and flow, rather than as a story with a “plot” and “resolution” because, frankly, there is none. To this effect, the cinematographers and editors should be given more credit than the actors.

This is probably one of the best ’60s-era hippie exploitation films ever made. I would highly recommend this film to not only pot-heads but also to fans of experimental cinema. But then again, what do I know? I’m just a Twenty-first Century new wave gangsta diva. Now let’s go chase that parade of technocolour ninjas riding emus.