Dateline: Downtown

Dateline: Downtown

September 23, 2007

Last week, we quickly covered the infamous doings that led to the construction of the present UMass Boston academic buildings. Do you want to know why the Wheatley roof collapsed last winter? Why the first result google gives you for “McCormack Building UMass Boston” reads, “”Transformer Fire Closes McCormack Building”? Why several rooms in the Science Building leak, why your DeLorean will be parked outside next blizzard?

Look no further than the pale ghost of now-defunct New York architectural firm McKee-Berger-Mansueto and the good-old-boys of the bad old days at the State House. A few thousand dollars in the right slimy pockets brought us where we are now, but it also brought us a department solely devoted to stamping out corruption in Massachusetts, the Inspector General’s. The Big Dig evinces a wince of recognition, yes, but when the Inspector’s office was established in 1981 it presented a bold challenge to Beacon Hill legislators who had been greasing squeaky wheels for generations. Michael Dukakis, who was Governor during this time, didn’t accumulate enough political capital to run for President by commandeering tanks or meeting people on the Green Line. His appeal, in part, was due to his effectiveness in stamping out the pay-to-play way of civic construction.

Subpoenas with teeth tore out of his office and sank into the careers of guilty parties like shady Republican State Senator Ronald MacKenzie and his Democratic camerado Joe DiCarlo, who were crushed by the wave of anti-corruption anger that swelled upon the impact of the 2,000 page Ward Commission report. The Commission halted the cash flow generated by bidding deals between private building contractors and the State.

The Commission was effective and widely respected. Thomas E. Dwyer, a founding partner of the law firm Dwyer & Collora, told the Globe last year that while he had seen ballyhooed oversight posses arrive before only to slink into obscurity, “the only one that survived with its reputation intact is the Ward Commission.”

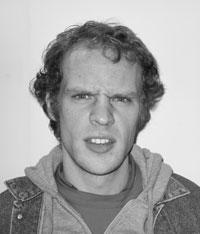

He credited John William Ward with the success. Ward, a teacher, carried an impressive curriculum vitae: the fourteenth President of Amherst College was named a professor at Princeton at 30; he was a pioneer in American Studies whose work explained the social significance of Presidents such as firebrand Andrew Jackson and anarchists like Alexander Berkman (lover of Emma Goldman and would-be assassin of industrialist Henry Clay Frick).

A scholar of such imagination as Ward seems an unusual choice to lead the dour bureaucratic death squad the Commonwealth needed, but let us look deeper: a memorial article published in a 1986 edition of American Quarterly upon his death in 1985 notes, “‘Bill’ Ward, as he was called by all who knew him even casually, was born in a lace-curtain Irish neighborhood in Dorchester, Massachusetts.” He was educated at Boston Latin, and then at Harvard. He was from here. Also, he was a Marine during World War II.

Bill Ward, then, came home to kick ass.

Because, while he was a big-picture provider in his field, he didn’t stay cloistered and sorting parchments. He was possessed of a social conscience. Arrested in a sit-down demonstration at Westover Air Force Base in 1972, a contemporary issue of Time quotes, “I do not think that words will change the minds of the men in power, and I do not care to write letters to the world. What I protest is that there is no way to protest.” He was the only University President in America to be arrested for protesting the Vietnam War.

It was this mix of steely conviction and home loyalty that led Ward to organize the Commission. He might not have been able to stop the war, but he could help disperse in the “everything a deal, nothing on the level, no deal to small” plague cloud on the Hill. His professorial talents must have served him well, both in compiling the report and leading investigators, a task akin in his words to that of “a teacher running a seminar, trying to keep the group focused.”

He was also a crafty adversary in hearings. The Globe described him in 1981 as “a courteous but tough interrogator.” A nice guy, in other words, until you piss him off. The Inspector General’s government website says: “The Office was established in 1981 as the first statewide inspector general’s office in the country. It was created in the wake of a major construction procurement scandal…The Commission found that billions of dollars had been wasted on building projects. The 12-volume Ward Commission Report concluded that: 1) Corruption was a way of life in the Commonwealth. 2) Political influence, not professional performance, was the prime criterion in doing business with the state. 3) Shoddy work and debased standards were the norm.” That was Ward talking.

As you trip over the cracked concrete on your way out of Quinn, take a second to think about why our buildings are the way they are. Look out onto the bleak grey patio and take solace that, at least, somebody went down for creating such an eyesore. The Inspector General’s office has your back.

One may point to the Big Dig with questions about the Commission’s ultimate effectiveness in stamping out Massachusetts corruption, but the extortionist MacKenzie anticipated them: “your successors will be here 10 or 15 years hence attempting to remedy new ills produced in large measure by the same old causes,” he said during a 1981 hearing. Sure enough in 1998 Robert Cerasoli, the first Inspector General placed by the Commission, was unleashing blistering appraisals of the handiwork of Bechtel and their Big Dig pig co-conspirators, noting “poor design specs,” “unclear testing procedures,” and “improperly installed anchor bolts” in the Ted Williams Tunnel where Milena Del Valle was killed. When you’re out by Quinn, remember her, and consider that maybe Bill Ward’s work isn’t done.