“I’ll never forget that day.” Professor Paul L. Atwood recalled, when we spoke over video call shortly before Thanksgiving 2020. “We were seeing a lot of problems, you know, and there were a number of suicides.” In the aftermath of the Vietnam War, he was the Director of the Veterans Upward Bound Program at UMass Boston, helping our returning veterans manage their physical and emotional wounds, and readjust to civilian life. Although he had been against the war, he was dedicated to helping returning warriors. One day a troubled veteran walked into his office, “he closed the door, walked up to me, pulled out a 45. caliber pistol and put it up to my head. He then put it under his… like this,” he said as he motioned mimicking putting a gun under his chin. Professor Atwood was a Marine, used to remaining calm in extraordinary situations. “And, I said ‘You know, if you do that, you’re going to spoil the paint job in this office’. I guess that disarmed him, he started laughing,” They spent the next three hours talking, and he was eventually able to bring in the programs’ councilor and campus police to assist in getting the troubled young man to the Veterans Administration Hospital in Bedford, MA for treatment. “A lot of these guys were having real problems adjusting to civilian life, adjusting to the university, not able to take stress of any kind. And it was a real wake up for those of us involved.”

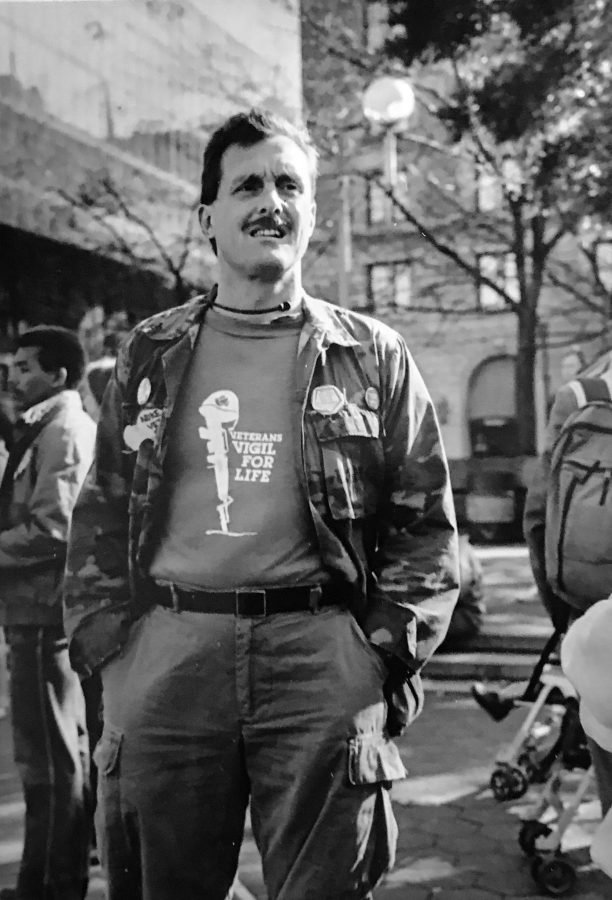

Professor Atwood appears outwardly intense, with deep laugh lines that bracket his mouth and his “military” style moustache. Likely due to a lifetime of working with veterans and teaching, he is surprisingly easy to talk to and is passionate about educating the next generation about the consequences of war. He encourages his students to critically analyze the narratives that we are expected to believe as Americas, especially the myth of our society’s “peaceful” nature. His 2010 book War and Empire: The American Way of Life is a study that contextualizes our history within the almost constant state of conflict we have found ourselves in since our country’s founding. He systematically makes a case for the falsehood of America as self-identifying as a reluctant combatant, being innocently dragged into conflict by unstoppable external factors. “I think most Americans believe that war in America is an aberration, but, as I’ve tried to argue in my book, it is anything but. War is the American way of life.” He reminds me our nation was started by a war, and has outwardly expanded militarily ever since, “That’s why we have 800 military bases around the world. That is why we are always intervening in somewhere or other. Citizens owe it to their country and themselves to face the real reasons the U.S goes to war.”

He is from a military family, his father serving in the US Marines during WWII in the Pacific theatre, his mother serving as a Navy W.A.V.E. (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service), his brother was a soldier, and he himself was a Marine. In today’s polarized political antagonism, an anti-war stance may draw criticism of being soft or having a “bleeding-heart”, you would be wrong in assuming that about Professor Atwood. In 1991, UMass Boston had a “free expression wall” on the first floor of the McCormack building. A student that didn’t like his anti-war stance wrote on it that Professor Atwood should be lined up against the wall and shot. Professor Atwood didn’t even ask to have it taken down, he wanted people to read it. He feels he has something important to teach the students coming through his classroom, and he is going to tell you what is on his heart and mind whether or not you like or agree with it.

As a conscientious objector, he refused to fight in Vietnam, and after disillusionment with his time in the military, he became an anti-war activist. “I came to the conclusion that the war was immoral, and it was illegal, and it was wrong, and I wasn’t going to have anything to do with it.” At a demonstration in New York City in the late 1960’s Atwood recalls, “I encountered Vietnam Veterans Against the War [VVAW], and so I hooked up with them right away, and I was very active, and have been active with Veterans for Peace ever since.” As a student at UMass Boston, he was very active with the VVAW on and off-campus activities, and after getting his Master’s Degree, he ran the Veterans Upward Bound Program here. “We don’t have a Veterans Upward Bound Program anymore at UMass, but at one time we did, and it was very instrumental in preparing veterans to move into the university and succeed. During that time, I became aware of the difficulties that veterans were having.”

According to Professor Atwood, in the early eighties, “about 10% of the [UMass Boston] student body were veterans, and many of them were anti-war. They wanted the William Joiner Center to open in order to deal with the aftermath of the war: PTSD, drug-abuse, suicide, you know, the litany.” He and many others successfully lobbied the State House to create the Joiner Center, and along with a tenured professor, he was one of the first co-directors. “All of this came together and there was a lot of real support on the part of Beacon Hill and Washington veterans to get us going . . . At the time the legislature was filled with veterans, either of WWII, or Korea, so they were very sympathetic to the idea.”

Regarding the work that the Joiner Institute has done over the years, he says, “I think most of the veterans that passed through the portals over the years, and there were thousands of them, had a positive experience of one kind or another, and there were many different kinds.” He is most proud of the important role the center played in in the eventual normalization of relations between the United States and Vietnam, “A number of our members, especially Kevin Bowen, Nguyen BA Chung, and David Hunt of the History department went to Vietnam, encountered many of the emerging writers there, and began to facilitate this normalization. Then Senator Kerry got on board with that and he talked to John McCain, you know, pretty soon, by the early nineties, 1994 or so, normalization had occurred. That wasn’t the only thing we did by any means, but you know I am particularly proud of that.” Although he hasn’t had any administrative duties at the Joiner Institute since he retired six years ago, he is confident that the “Joiners ability and willingness to help veterans hasn’t changed.”

“Immediately after the [Vietnam] war ended, there was this great silence, people wanted to push it aside and forget about it, but then all the problems began to emerge among the veterans themselves. In the 80’s people were becoming aware of the problems that veterans were having, and re-evaluating, I guess, the Vietnam War.” Then after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the ensuing wars, “a whole new set of problems and a new set of veterans emerged.” Building tensions between the United States, Russia and China are concerning to Professor Atwood “Every course I taught was either in the American Studies Department or at the Honors College. All of them were developed out of my concern about war, the American way of war, and the Jointer Center was very helpful in helping me do that research.” Having spent a lifetime dealing with some of the worst aftermaths of war, both with, and alongside veterans, he warns, “war brings out the worst in human beings, no question about it, and when they come back, they’re going to have trouble, serious trouble. So, you think about that before you urge your sons to go off to war. We claim to care about that, but then why do we keep sending them off, for what? What payback do they really get? A couple of medals? A flag at their funeral? I don’t get it, I really don’t. I think people just freeze it out, they don’t want to think about it. That is exactly why we are so easily misled.”

Reflecting on the chaotic year of 1968, he tells me “Ironically, I escaped going to Vietnam, and I come home, and I get shot on the streets of America.” It was the day after his 21st birthday, and he had just enrolled at UMass Boston. Heading to a shift unloading meat trucks in the old Quincy market, he was running to catch a streetcar on Huntington Ave, “right in front of Northeastern University, and my leg blew out from underneath me. Then later I found out these other people had been killed.” In random acts of violence, a crazed gunman shot him on Huntington Ave, and killed two other people on Mass. Ave the same day. The shooter was black, and all the victims were white, “it was a product of the racial insanity of the time.” He says, “I will never forget lying on the sidewalk on Huntington avenue in front of Northeastern University with my leg broken in two, and blood pooling on the sidewalk, and people walking by.” No one stopped to help him, “I kept thinking any minute now an ambulance is going to arrive right? I lay on the sidewalk for close to an hour, until this little black kid came along and said mister what happened to you? I told him to run inside and get the Northeastern University police, get someone to call an ambulance.” Before the good Samaritan left him to get help, he took off his jacket and made a little pillow for his head. Professor Atwood’s gaze drifts. He pauses and says, “He didn’t see a honkey lying on the ground, he saw a human being in trouble.”

About five days later, detectives came into his hospital room and said “We got the guy, they showed me a photo of the guy, and said we want you to sign this statement saying this is the guy that shot you. I said well, I didn’t see it. I’m not signing it. They said just sign it, if we don’t get this, the judge is going to throw it out in court. I said I’m not signing it, I didn’t see the guy. The cop said kid, he’s just a fucking n*****, sign the thing. That is the context of this whole thing.”

Regardless of your opinion of Professor Atwood’s political or social views, you have to admire a person that has consistently and steadfastly stood up for their beliefs in such a way. He refused to fight in a war he felt was unjust yet fought to serve the returning warriors of that very conflict. He teaches and writes what he believes, regardless of the professional or personal consequences. And in a time and place where it would have been easy to give into bitterness and a desire for revenge, he chose integrity and refused to sign the statement being pushed on him.

Two weeks after being released from a year-long course of treatment at the VA, the troubled Veteran that brought the gun into Professor Atwood’s office killed himself. The man that shot Professor Atwood on the street and had killed two other bystanders in 1968 was found insane and was committed to the Bridgewater Prison for the Criminally Insane, now called the Bridgewater State Hospital. When I asked about how Professor Atwood felt about the man that had shot him, he said “I would’ve liked to have talked to the guy.”

For the Faces of UMass Boston: a conversation with… Series we ask all of our guests to fill-in-the-blanks of this question. Here is Professor Atwood’s answer:

I always feel [nervous] in a room full of [students I’ve never met before].

Sources:

Based on information gained from a video call interview with Professor Paul L. Atwood on 11/18/2020.