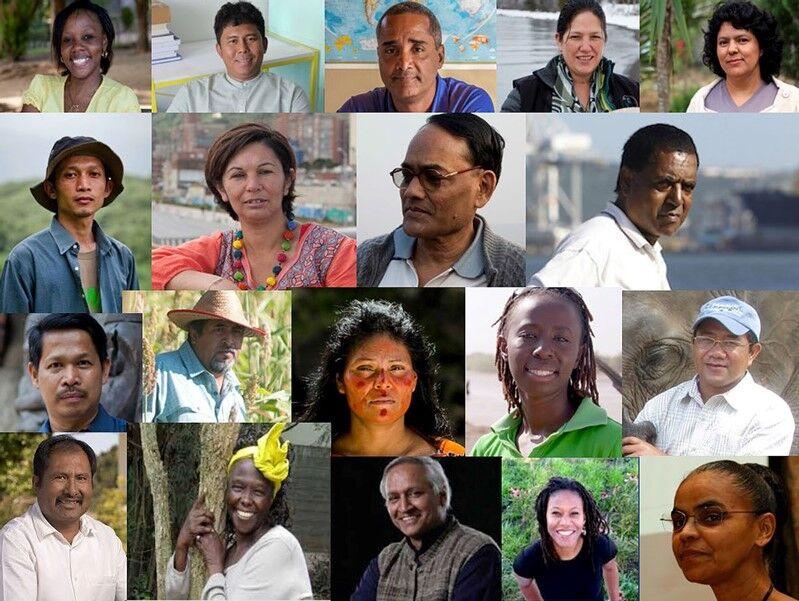

In interactions with students through my Global Ecology course at Boston University for many years and in 2018 here at UMass Boston School for the Environment, I realized that something I was emphasizing is actually seldom found in University and high school curricula. It became clear that there has been little attention given to the many science-based, grassroots leaders—most of whom peoples of color—around the globe who through their thinking and actions are prioritizing their home, Earth, and from whom we in America’s communities could learn a great deal.

While they may not all use the terms “ethics” and “biosphere,” these leaders are for the most part practicing an Earth-centered ethic—that is they know that without a healthy environment (biosphere), there is at best an often tenuous today and surely a tragic tomorrow. They know that the human species and many essential life forms (bees, whales, butterflies, etc.) and ecosystems (rainforests, estuaries, etc.) are symbiotically intertwined as a kind of intimate ecology, both locally and on a global scale, that has been deeply disrespected within our ways of thinking and living.

In addition, I found that while human-caused climate change and environmental degradation are commonly central and surely essential in environmental and now even social studies courses, the realization of dynamic connections over vast distances in the biosphere—nature’s profound “global ecology”—are often only touched upon.

My Global Ecology course, which uniquely features these two eye-opening realities, has unfortunately been left off the UMass Boston course agenda for the past two and a half years, despite its profound relevancy to two current, ongoing crises: (1) the continuing policy and societal disregard, intentional or not, for Nature, upon which we all completely depend for our current and future well-being; and, (2) the continuing devaluing and even denigrating of peoples of color including indigenous peoples by many citizens, especially those who subscribe to white supremacy or white privilege.

Not only is the course quite revealing and even inspiring to some, but it is connected to my Global Ecology Education Initiative wherein I voluntarily and periodically give invited presentations at metro Boston high schools and community settings. When the course was last offered here, as well as in my many years at BU, I was often able to bring along a student or two from the Global Ecology course who would join me in giving the presentation and thereby further impact and serve as models for the younger students. This potential has also been made absent even well prior to the pandemic.

I realize that my expressions here can surely sound naive or simply too self-centered, for many other professors or instructors could very well cite their demoted or sidelined course and/or its importance. And, we can certainly point to the financial issues of this University and all that the new, highly experienced and highly-regarded Chancellor has to face budget-wise, and organizationally. But, this or any university has to be careful that the business model does not necessarily overtake the education priority. Despite what some may say, emphasizing only those courses that will have 50, 100 or more students enrolled may bring in or allow greater financial gain, but ultimately most students seeking high quality, somewhat personalized and dynamic engaging learning situations, prefer universities that offer small-size class options.

Bottom line, even if the sidelining of Global Ecology is permanent, the inclusion of leaders/peoples in the world who are practicing earth-centered ethics and actions in courses generally is an educational imperative if we want to be serious about prioritizing the building of a viable, nature-respecting, and biodiverse future.