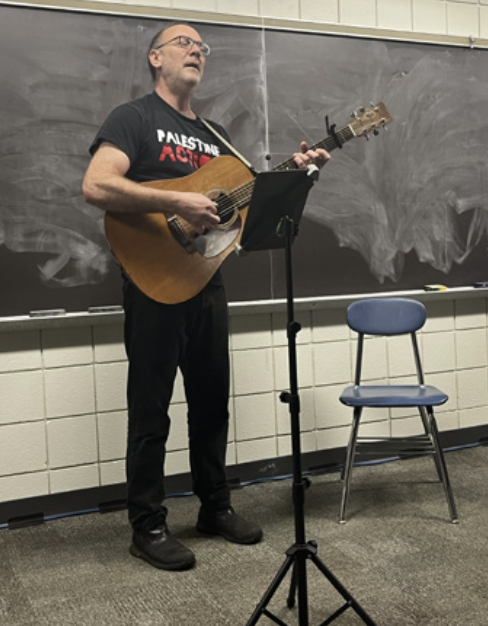

David Rovics, a musician, writer and podcaster based in Portland, Ore., performed in Phillis Wheatley Hall March 29 as part of his Bearing Witness tour. Rovics, who has toured in over two dozen countries, is a self-proclaimed anti-war and anti-capitalist activist, and his songs cover a wide range of protest movements and current events. Most recently, Rovics released an album titled “Notes From a Holocaust,” which covers what he describes as the “ongoing genocide of the Palestinian people.”

At the concert, Rovics established that while overtly political songs may be “exotic” in America, he describes his style of music as “part of a long-standing tradition in other parts of the world.” He cited musicians and artists such as Mahmoud Darwish, a Palestinian poet who writes, like Rovics, about the Israeli occupation of Palestine.

In that spirit, Rovics began with a song from “Notes From a Holocaust” titled, “Baby Jesus Lying in the Rubble.” The song contrasts the religious significance of Jerusalem with the devastation being rained down on Gaza. He sang, “There’s Baby Jesus lying in the rubble / A hungry little bag of skin and bones / With his mother Mary broken there beside him / In the place that they were calling a ‘safe zone.'” He also played a variety of anti-imperialist songs about countries around the world, from Scotland to Chile to Vietnam.

Rovics got his start in the 1970s and ‘80s, when his parents, both of whom were musicians, introduced him to singer-songwriters from the anti-nuclear movement. He said, “That was my first exposure to this kind of music and to how powerful it can be as a means of communication and inspiration.”

From there, Rovics was introduced to what he called “The Movement,” with a capital T and a capital M. He explained, “It meant the anti-war movement, the anti-capitalist movement, the anti-nuclear movement, the feminist movement, the gay-lesbian movement and so on.” After that, it wasn’t long before people in The Movement expanded their activism to Israel-Palestine.

Since then, no activist movement has reached the same heights as The Movement, Rovics said. According to him, part of this decline can be attributed to the advent, and later monetization, of the Internet. “Around 1995 to 2005 was a golden age for the internet, for organizing online and using those resources effectively. And from the time Facebook came around, they’ve been undermining and destroying all that to the point where now it’s just a real dystopia, where people haven’t grown up entirely in reality.”

At the event, Rovics went into more depth about how social media has affected his life. He detailed the consistent harassments he has faced by what he calls “Hasbara trolls”: supports of Israel who are “consistently racist, sexist and homophobic, even the so-called ‘leftists.’” Despite being Jewish himself, Rovics has been labeled as anti-semitic for his activism surrounding Gaza, which he reflected in his song fittingly titled, “Antisemite.”

He also spoke about the effect that the internet has had on independent creators. Before the 2010s and the advent of free music streaming, musicians could leverage their ability to give out free music and draw people in. “Before Spotify started their free tier, I was selling 3,000 CDs in a typical year. You know, that’s $30,000 just from CD sales. And then suddenly from one year to the next, it went from that to just about nothing… There’s no way to make money running a little record label.”

The music industry as a whole, according to Rovics, isn’t free from bias. He described the current state of the industry as “systematically racist,” especially how music is categorized into genres. The industry groups musicians into arbitrary collections based ostensibly on tone, but in reality, many of these genres are race-based. Throwing off any genre labels, Rovics said at his concert, “I just prefer to write songs about everyone else—everyone that Western media ignores and dehumanizes.”

Rovics hopes that his music will inspire people in the same way that The Movement inspired him decades ago. He said, “I’m always hoping that my music will educate people about a lot of things they didn’t know about, will inspire them to act and do something about the things I’m thinking about—these days, that’s often Gaza. And I’m hoping that my music will help break down the isolation that people feel for so many different reasons and bring people together.”