PIRGs, Publishers At Odds Over Textbook Prices

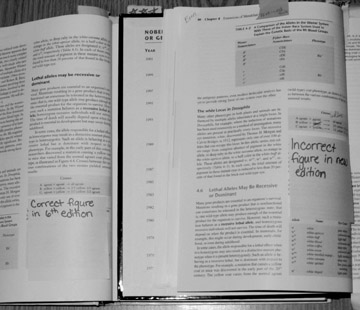

Errors in a new genetetics textbook found by professor Richard Kesselli.

May 1, 2004

Astronomical textbook prices are no accident, says a new report put out by Public Interest Research Groups nationwide. The PIRGs are organizing a campaign to fight what they call price gouging and unfair business practices, and they’ve got students and professors behind them. But textbook publishers adamantly deny their prices are unfair, or that they are profiteering off a captive market.

“The report shows some of the ways in which the textbook industry marks up prices,” says Eric Bourassa, consumer advocate for MassPIRG, which held a press conference Thursday to release the report. “The bottom line is that students are getting ripped off by the textbook industry.”

Textbooks are overloaded with “gimmicks,” Bourassa explains, “shrink wrapping, adding CD-ROMs and other additional materials-the majority of the professors surveyed don’t actually use that material. And when the textbooks get updated, the majority of the faculty felt that the updates were unjustified.”

However, Thomson Learning representative Adam Gaber says the report is full of inaccuracies and he rejects the idea that publishers are taking advantage of the market. A Thomson Learning textbook was singled out in the MassPIRG report as an example of unfair pricing.

“First off, it’s important to understand how much textbooks have changed since the days of one-color, copy-heavy books.” said Gaber in an email, “Both students and professors demand more and more access to technology to improve teaching and learning. While these additional resources greatly enhance the value of textbooks, they also drive up the costs of developing, maintaining and supporting the modern textbook.”

The report claims that publishers deliberately put out new editions and discontinue older ones to prevent students from buying substantially cheaper used books. UMass Boston Professor of Mathematics John Lutts explained the problem with two Thomson Learning calculus books. “This is the fourth edition and this is the fifth; there might be a five page difference in there,” he said, holding books side by side.

Professor Lutts said that he has no reason to switch books, but it can’t be helped. When an older edition goes out of print “we’re at the mercy of the publishers.”

Gaber says that new editions are crucial to keeping up with advances in technology and academic discipline, “The average revision cycle for a textbook is four years. Ten years ago the average was just under five years. Given the information explosion of the last decade and advancement of teaching techniques brought on by the rapid evolution of technology, it’s not surprising that the revision cycle has shortened.”

Another way that students lose out is that textbooks can be bought in other countries for steep discounts, often as much as half the price of the very same book on an American campus bookstore. A calculus textbook published by Thomson Learning goes for $122 in the U.S. and can be found in Britain for the equivalent of $59 dollars.

Susan Smith, a student senator at UMass Boston, was upset by the difference in prices, “They sell textbooks in Canada and the UK for half the price. It reminded me a lot of the prescription drug problem. Are we going to have to go across the border to buy our textbooks?”

Gaber explains that lower overseas pricing is a necessary part of doing business, and that publishers “carefully examine the social, political and economic realities of foreign markets (e.g., average per capita income, standard of living variances, comparative costs of other goods and services, tuition rates, government education policies, financial resources available to students, etc.) to establish fair prices for textbooks in foreign countries.”

Gaber also points out that the Thomson Learning book cited as overpriced in the report could be called a bargain, “while the book does cost $101 net price, the course itself is three semesters in length so … a student is actually paying $33 per semester.”

So are textbook prices fair? MassPIRG doesn’t think so, and many students are struggling under the weight of textbook costs, which are rising. But the textbook publishers say that new technology and new teaching methods demand they keep up.

According to the report, which surveyed 10 public universities, students now spend an average $898 dollars per year on textbooks, up from $642 in 1997. Smith says she “spent close to a thousand dollars in the last year at the bookstore. I figured out that’s 17% of my tuition. Textbooks you can’t really finance. You have to pay for them all at once; a lot of people are putting them on credit cards.”

The PIRGs wants textbook publishers to make textbooks available “a la carte,” so students can choose to pay for extras like CD ROMs and study guides, and wants publishers to keep older editions on the market as long as possible, so cash-strapped students can buy used editions whenever possible.