How to Remember; How to Tell

for more info visit www.asenseofduty.com

May 17, 2005

By Yasuhito YamamotoStaff Writer

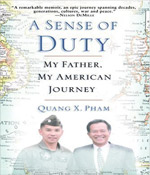

It’s been thirty years since the fall of Saigon and the beginning of Vietnamese refugees flight to the United States. Are they simply historical events, engraved in history books? On May 3, the Asian American Studies Department hosted an event, “Thirty Years after Vietnam: Myths, Lessons, and Closure,” featuring Quang X. Pham, author of the newly-released book, A Sense of Duty. This event was a part of his national book tour, and UMB was his Boston stop.

“There is a gap between parents and younger generations,” says Pham about one of difficulties he encountered during his writing. “Younger generations want to know more, but don’t know how to get information. History books don’t show what their parents really have experienced.” When Pham asked older generations about their experience, “some started crying and others stopped talking.” When asked how he then managed to gather words from them, Pham answers, “So, instead of asking to tell what they have experienced, I said ‘What would you like to tell your kids? What would you like to tell Americans? How would you like them to remember?’ Then, they started talking again.”

During the event, various perspectives toward the war and refugee experiences became apparent. In the United States now live Vietnamese who fought in the war to prove their American citizenship, Vietnamese who came as refugees after the war, non-Vietnamese Americans who fought in Vietnam, and Americans who went to and served in Vietnam after the war. They all have their own understandings of the war. At the end of the event, one audience member asked, “How do we know what we should remember? How do we know what things are correct to remember?”

“I think we should appreciate each person’s memory. I used them to do a frame work [for my book], and then connected them to my father’s experience,” says Pham.

These things above are also the issues that many immigrants’ families face, and thus, in order to remember and pass the experiences down, we need someone who can interchange between the two, and we also need a space where families can share their perspectives. In this event, Vietnamese veterans, their children, and grandchildren attended, allong with many UMass faculty members and students.

Peter Kiang, professor of education and director of the Asian American Studies program, expressed his appreciation for UMass Boston’s understanding of this event’s importance. As we all know, UMass has a diverse body of students along with diverse faculty members and programs. Nonetheless, to reflect the attitude of this country, so-called “minorities” have been neglected. For instance, we see lots of Vietnamese students at UMass. Why don’t we yet have a Vietnamese language course when we have Chinese, French, German, Greek, Italian, Japanese, Latin, American Sign Language, Russian, Spanish, and English? It is important for UMass to offer a space where students and communities meet and share their perspectives, which will make up for the gap between generations.

When opening a history book, anyone can find the fall of Saigon, the capital of then-South Vietnam, in 1975. Yet, its after-effects still remain in our society, three decades later. It has been 60 years since the atomic bombs were dropped. It has been two years (do we remember?) since the beginning of United States’ official threat of an invasion of Iraq for the cause of “Iraqi Freedom.” We must acknowledge it, remember it, and tell it.