It is Success – He Will Not Be Execute

Photo Courtesy of 20th Century Fox

November 7, 2006

Borat is dead.

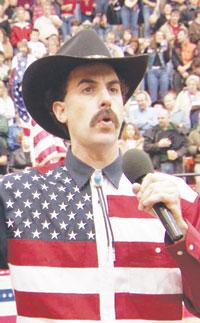

Or at least he very well could be, now that his soon to be hit post-summer comedy blockbuster movie, Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan has hit theaters across the county. Unfortunately the subject that might eventually spell the death knell for comedian Sacha Baron Cohen’s bumbling Kazakhstani reporter is not going to be a crowd of irate Virginians offended by his butchering of the National Anthem. Instead it might be the very popularity, or infamy, that the films protagonist Borat Sagdiyev has been generating even before the film has been released.

The debates have already started brewing over weather the film is a brilliant piece of comedic cultural satire, or just an insensitive, sexist, racist, homophobic, xenophobic, chicken-abusing slab of shock-cinema.

The nation of Kazakhstan seems to agree with the latter. The Kazakh Foreign Ministry has threatened to take legal action against against the producers of Borat for what they see as a derogatory depiction of Kazakhstan.

Cohen plays the role of Borate, a Kazakhstani reporter who is traveling the “US and A” to bring a broader sense of cultural understanding to the people of Kazakhstan (a rough translation for those of you who were unable to make it through the broken English of the film’s title.) Though the film presents itself as a fake documentary, a mockumentary if you will, its not quite the staged effort that many other fish-out-of-water flicks of this type are.

Borat is a fictional character, a creation of English born Jewish comedian Sacha Baron Cohen, who has used the character before in his British television show, Da Ali G Show, which go on to become a minor hit when it was broadcast in the US on HBO. But most of the other individuals featured in the film are not professional actors, they’re not even amateur actors, or even acting at all. They are average citizens, people on the street, and the heads of New York’s Veteran Feminists of America.

Cohen via Borat presents himself as a humble reporter from some far-off underprivileged former Soviet country. His rumpled suit, bushy mustache, and heavily accented broken English don’t seem to suggest otherwise, and so it is in this guise that the character of Borat is able to sit down with a group of New York Feminists and talk about issues related to woman. The interview starts our innocuous enough, Borat introduces himself with his trademark, “My name a Borat” and he and the woman begin to talk about issues. But the interview quickly stars to get awkward for the guests, to the delight of the movie audience, as Borat’s stats to expose his country’s apparent backwards notion of female equality. He brags about how his country’s woman pull the plows and how they must walk three steps behind the men as “it used to be 10 steps, my country is advancing.” At first the woman try to help Borat realize the advances made towards woman’s rights in the US, but by the time he is able to ask if women do in fact have smaller brains then men, he is kicked out and not welcomed back.

Many people will see that Borat’s ignorance portrayal as merely a ruse, designed specifically to get a reaction out of both his guests and the audience. Often he is able to expose that the true ignorance is already around him. When talking to a Tennessee rodeo manager, Borat is able to relate through their shared distrust for both Muslims and homosexuals. Once again, Borat is merely a character; the unfortunate rodeo manager is what he is.

But also many will see his intense cultural insensitivity, such as his adamant anti-semitism as functioning as little beyond reinforcing already existing stereotypes. The film opens up in Kazakhstan displaying the nations culture with their annual “Running of the Jew,” a public celebration where citizens are chased by a man in a giant troll mask. Later on, while traveling through Atlanta, Borat approaches a group of tough looking black youth who are playing a game of craps against a wall and innocently asks “How can I be like you?” Knowing that these gentlemen don’t seem to be the type to be interested in playing games, most of the audience is on the edge of their seat for fear of not Borat’s but Cohen’s life.

Cohen’s strategy depends largely on awkwardness and uncomfortableness, and though many of the scenes intentionally to go to far, they manage to extend the same sense of uneasiness right onto the films viewers themselves. Call it just deserts if you will. There is one scene where Borat, upon exiting the shower, catches his camera men “enjoying himself” to a copy of a Baywatch picture book that contains the love of his life: Pamela Anderson. Short of giving away all the details, lets just say its an extended fight scene in which you’ll wish for more generous use of black modesty bars.

In a way this schtic borrows heavily from other provocatives like the Daily Show, Tom Green, and Andy Kaufman who utilize the improvised reactions of clueless passerby. Like Kaufman, Cohen’s no on-trick-pony who has a grab bag of characters that he is able to tap into to keep the laughs original. But he also might soon be struggling under a career trajectory like Tom Green’s, Cohen’s already utterly offense shtick might cross over into the realm of intolerable as his notoreity grows, his pool of usable targets shrinks, the inspiration dwindles, and he must eventually resort to taking pot-shots at obvious and easy targets like the elderly and non-English speakers. You can’t be famous and incognito at the same time.

So far Cohen and his Borat character seem to be riding high as the debates revolve not around whether the joke is funny or not, the film is a near wet-your-pants laugh fest, but in whether or not viewers are able to make reconcile with his bigoted ignoramus persona.

Chances are as long as your not the Kazakhstani government you should be just fine.