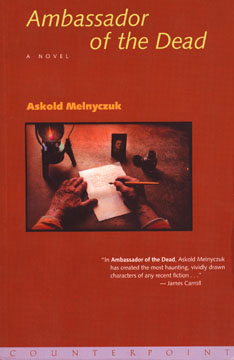

Ambassador of the Dead

April 9, 2003

Askold Melnyczuk’s 2001 novel, Ambassador of the Dead, is the odd heir of a new genre of exploratory novel, the second-generation holocaust memoir. Ambassador tells the gripping, late in life bildungsroman of Nicholas Blud, son of post-war Ukrainian émigrés to America. The narrative takes shape in several nesting stories, as Blud, mysteriously called to aid a childhood friend, is regaled by his friend’s mother, Adriana Kruk, with stories from her past.

Melnyczuk, Professor of Creative Writing at UMass Boston, has crafted a book that seems like a series of dreams, an effect that is deliberate, and powerful. Called by Ada, ostensibly to help her son, Alex, Nicholas instead finds himself listening to Ada spin out a story of her childhood in the Ukraine, while Alex, Blud’s old friend, lays dying in the next room. Underscoring the narrative are Blud’s own memories of the Kruks and of Ada, who gave him a sexual initiation as a very young man, and whom he is terribly ambivalent about. This tension runs throughout the book like an erotic cord, coloring his own memories and Ada’s stories with a sultry and occasionally disturbing sensuality that contributes to the dreamy quality of the narrative.

Alternately relating Blud’s teenage memories of growing up the son of immigrant parents and Ada’s stories of her and her family trying to leave behind the Holocaust and a shattered Old World idyll, Melnyczuk matches their tone and pace admirably, imparting a simultaneous sense of myth and human weakness to the whole book. The occasionally halting, disjointed narrations remind the reader forcibly of the truth of memory, that it is a fickle and subjective thing, fit for telling stories and rendering emotions in shades of sunlight and seasons, but not for granting understanding or reconciliation. This quality of frank truth in narration is what recalls it to classic Holocaust narratives and fiction. It’s an unwillingness on the part of the author to grant absolution or give meaning to his characters, his readers or the world that perpetrated World War II.

In a world without meaning, and in a time without borders between yesterday and today, caught in the traps of their own consciences, Melnyczuk’s Ukrainian refugees cultivate their own order, clinging to their expatriate community and determinedly chasing the American dream. Their sons and daughters enjoy a weird freedom, a cultural distance from their own parents that Melnyczuk frames in a subtle fashion, surrounding it with the callow sensuality of youth and allowing the reader to see into and above his characters. Ambassador bears the imprint of the master storyteller; Melnyczuk never tells, only shows us, his tale, and the reader is free to be guided through a tale with no end and no real beginning and still feel that a service has been rendered.

The plot of the book is fascinating. All the action takes place between an old woman sitting in her chair and a middle-aged man, listening to her expose her life as her son lies dying in the next room. Everything else, the history we obliquely share in, the peachy romance of youth and the shattering violence of war, the torrid dynamics of family and friendship, and the knotty search of a rootless young man, take shape in the air between them, a confection of memory, truth and lies that is fervently genuine.

More fascinating yet is Ada, a woman whose family and memories burden her so excessively that she becomes an iconoclast and a misanthrope, propped up by her pride and determination. Unable to wall off her past as the others have done, scraping by with two sons and a profoundly damaged brother, Ada’s character invests the book with a shamanic, otherworldly presence. A bright, powerful woman, she’s trapped in her femininity and lack of education and ostracized from her fellow refugees, but perceives and understands everyone around her better than they do her, and her insight, which never approaches the unbelievable, is awe-inspiring. Ada has two American sons and had a passionate, unpleasant husband. Her sons go wild, with the disembarkment of the father, and much of the tragedy of the novel can be seen in the promise, the luminescence of the young Alex, and his mother’s hope, being dragged down by his wildness and anger. It’s never pretty when a mother outlives her son, but the rare gift of Melnyczuk’s novel is to make us understand them as people rather than just in terms of their relationships to each other.

So much of the book seems so genuine and true to life that the book takes on a life of its own. It’s not clear how much of this novel is autobiographical, but it really doesn’t matter; it might as well be entirely so. Some books feel as if the author has a story to tell, and you read the words in order to get to the voice behind them, no matter how well crafted they might be. Some books feel as they are a story that needs to be told, regardless of how the author feels about it one way or the other, and the writing can range from atrocious to inspired, but you are hearing the story through the words, and the author fades from consideration. Ambassador of the Dead falls into this category, and Melnyczuk is wise enough to step out of the way of his characters, and let them tell their tale. The book could have been tighter and neater, if Melnyczuk had wanted to push his people around, but he doesn’t. His characters are real people, as real as ever could be found in fiction, and they live in his book the way we all live in the real world, neither with an end nor a beginning, just as part of a story, sometimes yours, and sometimes someone else’s.

Askold Melnyczuk teaches at UMass Boston and is the author of another novel, What is Told. Ambassador of the Dead was one of L.A. Times’ “Best Books of 2002.”